Friday, March 29, 2019

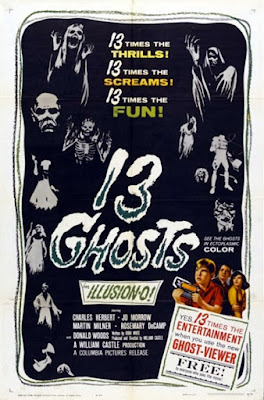

13 Times the Thrills! 13 Times the Screams! 13 Times the Fun? A Beer-Gut Reaction to William Castle's Illusion-O Fueled 13 Ghosts (1960)

We start at the Los Angeles County Museum, where Cyrus Zorba (Woods) is lecturing a group of students, focusing on the dangers prehistoric animals faced while getting swamped in the La Brea Tar Pits (-- which in no way should be interpreted as blatant foreshadowing for the haunted house flick we’re about to encounter. Nope. Nosiree). This lecture is soon interrupted by a phone call from Cyrus's wife, Hilda (De Camp). Seems museum curators don’t make all that much, and a collection agency has just reclaimed all of their furniture due to delinquent payments. And that's why their son Buck’s birthday is celebrated on the floor of an empty apartment, where the family gifts him yet another book of ghost stories.

Though his older sister, Medea (Morrow), chides him on his morbid reading habits, after presenting his cake and candles, they all ask Buck (Herbert) to make a wish. This he does, wishing for a big house, with lots of furniture, when suddenly, an ominous wind kicks up and blows Buck's candles out for him. (Editor’s note: This ominous wind blowing will be a reoccurring theme for the duration of this motion picture.) Then, fate knocks on the door: a messenger, bearing notice of a meeting with attorney, Ben Rush.

Fearing it might be yet another collection agency, Cyrus expects the worst but, instead, gets some good news. Well, sort of. First the bad news, as Rush (Milner) informs his new client that his estranged uncle, Dr. Plato Zorba, has recently passed away; but he left Cyrus, the sole heir, his entire estate, consisting of a very large mansion and a mysterious package. When asked if there are any liquid assets, Rush says even though Dr. Zorba was apparently loaded, he was also very eccentric, kept his fortune to himself, and, alas, took its location to the grave with him.

And while Cyrus and his wife are very excited about the prospect of moving into their new digs, Rush warns them against it; for it seems Dr. Zorba was deeply into the occult and collected ghosts. And these ghosts, as the rumor goes, still haunt the mansion. And like it or not, they’re part of the inheritance, too. But, the skeptical Zorbas cannot be dissuaded, and when Rush leaves to start on the paperwork to make this all official, Cyrus and Hilda turn their attention on the mystery package. When Cyrus breaks the seal, the wind kicks up again, ominously. (See! I told ya.) But! The package’s only contents are a strange pair of glasses. We’ll call them the X-Ray Specs. Discarded with a shrug, a plastic fly, on a very visible string, begins buzzing them, and when the faux fly lands on the X-ray Specs, it gets electrocuted. (Great. Uncle Plato left them his favorite bug-zapper.)

Time passes and the Zorba clan begin settling into their new home, which comes complete with furnishings and their very own maid, Elaine (-- the old Wicked Witch of the West herself, Margaret Hamilton). When Rush brings the last of the paperwork, Cyrus signs on the bottom line, making everything legally his. (I guess now is as good a time as any to point out Medea has a crush on the new family lawyer.) But the ink is barely dry before the ever-curious Buck finds an Ouija board ensconced in a secret compartment near the fireplace, which also contains the late Dr. Zorba’s personal diary. Hoping it might contain a clue to his hidden fortune, the answer will have to wait because all the entries were written in Latin. When Rush, perhaps a little too eagerly, offers to get this translated, Cyrus declines, saying he has a colleague at the museum who can handle it.

With that settled, thinking it will be a real hoot, they all decide to try out the Ouija board. First, Buck asks if the house is really haunted, and the board answers, 'Yes'. A few more questions reveal there are thirteen ghosts in total roaming the house. And then comes a warning that one of them is in mortal danger! When they ask whom (-- and there’s that ominous wind again, right on cue), Plato’s life-size portrait falls off the wall, barely missing Buck, and crashes to the floor. Then, the wooden planchette of the Ouija board goes airborne, on its own, and draws a not so subtle bead on Medea.

I'm guessing that was just too much for everybody, because they all decide to turn in soon after. Totally unnerved, and fearing for her children, Hilda wants to leave. But Cyrus breaks out the old rational scientific explanation speech to calm her down, adding they can’t just leave: seems there was a stipulation in Zorba’s will that they can’t just sell the estate but have to live there or forfeit it all to the government. (Man, that @#%* fine print gets you every time.) At Hilda’s insistence, Cyrus goes to check on the kids when he hears a ghostly wail coming from down the hall. Zorba's ghosts are definitely restless and on the prowl tonight.

Collecting up the magic X-Ray Specs, he traces the unearthly noises to a secret lab. And something is definitely in there with him but he can’t quite make it out -- until he puts on the goggles, which magically allows him to see several specters. Then, they all burst into flame before a fiery pinwheel attacks him, which burns the number thirteen onto the back of the witnesses hand. Not to worry, Cyrus, you dunderest of dunderheads, I’m sure there’s a rational scientific explanation for that, too...

A decade before 20th Century Fox unleashed Cleopatra (1963) -- the cinematic boondoggle to end all cinematic boondoggles, Columbia Pictures had told the same tale of the doomed romance between Queen Nefertiti and Marc Antony at about 1/10th of that film's budget (-- and without the backstage B.S. of its two main stars overshadowing everything else). Two years in the making, twelve days in the shooting, Serpent of the Nile (1953) is goofy as hell, sure, but speaking frankly, it delivers far more bang for its measly bucks than its bloated and overdrawn brethren. And while the movie plays out like a very elaborate SCTV skit, with Raymond Burr (John Candy) as Marc Antony, William Lundigan (Joe Flaherty) as Lucilius, and Rhonda Fleming (Catherine O'Hara) as Cleopatra, what else would you expect from producer Sam Katzman and, believe it or not, director William Castle.

Yeah, people tend to overlook Castle’s early film career in Hollywood and tend to focus more on his later horror movies and gimmick-driven output, which is too bad because the guy had a hand in damned near everything. Long before he started insuring audiences, wiring up seats, and floated skeletons over theaters, Castle started out at Columbia in the B-units, where he quickly earned a reputation for working fast and bringing his pictures in on time and under budget. Castle directed nearly all the entries in the mystery serials of The Whistler (1944) and The Crime Doctor, starting with The Crime Doctor's Warning (1945). Castle also kicked around at other studios, too, directing the unheralded and very idiosyncratic film noir classic, When Strangers Marry (1944), for the King Brothers at Monogram, which proved a bit of a sleeper hit at the box office and drew high praise from Orson Welles, leading to Castle’s eventual collaboration with him on The Lady from Shanghai (1947).

But after taking this brief hiatus from Columbia, which also included a string of noir pot-boilers for Universal International like Johnny Stool Pigeon (1949) and Undertow (1949), Castle migrated back to his original studio and started a five year (and nearly a dozen picture) odyssey under the tutelage of producer and notorious industry cheapskate, Katzman, and his merry band of filmmaking goons at Clover Productions, beginning with Fort Ti (1953), which technically, was also Castle’s first official foray into gimmick filmmaking since the film was shot in 3D; and just like with his later product, Castle doesn’t cheat his audience, exploiting this new stereoscopic process for all it was worth.

Castle shot several other westerns for Katzman and Columbia, too, including Jesse James vs. the Daltons (1954), also in 3D, Battle of Rogue River (1954), and The Conquest of Cochise (1953) to name just a few. There was also the medieval fantasy adventures of The Saracen Blade (1954) and The Iron Glove (1954), swashbuckling tropical intrigue with Drums of Tahiti (1954), and rip-snorting adventure yarns like Charge of the Lancers (1954) -- all of them done on a dime. And who could forget Castle’s lone biblical epic, Slaves of Babylon (1953), where we get Cecil B. Demille on a Sam Katzman budget with their take on the tale of Daniel in the lion’s den mixed-in with a plot to overthrow King Nebuchadnezzar as told in the Book of No Not Really: Chapter 2: Verses 1-5.

Yeah, Castle’s earlier oeuvre deserves a serious look and further exploration, but not today. Nope. We're here to once more celebrate the ballyhoo and the bullshit of Castle’s raison d’etre. As the legend goes, Castle was intrigued by the huge success of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s imported thriller, Diabolique (1955) -- especially it’s twist ending, and the promotional efforts that not only teased the frightful climax but at the same stroke worked very hard to keep that final shock / reveal a secret. But most important of all, Castle was keenly interested in the massive lines forming around the block wherever the film played.

And with that inspiration Castle decided to try his hand at producing and financing his own fright flick, Macabre (1958) -- a tale of kidnapping and buried secrets in a small town; and to ensure an audience draw, Castle hit upon a notion to insure the audience against “Death by Fright” offering $1,000 to the family of anyone who keeled over before the end credits rolled.

And when that proved a hit, then came Emergo for House on Haunted Hill (1959), which saw a skeleton flying over the audience during the climax, and Percepto for The Tingler (1959), which saw audiences getting a strategic jolt whenever the beast got loose. (A film I’ve seen in a revival theater, and at a drive-in, and got to scream for my life. Twice. It was magnificent.) Which brings us to 13 Ghosts (1960), and Castle’s latest concoction: Illusion-O.

Kind of a 3D knock-off, audiences were given a 'Ghost Viewer' when they entered the theater, which contained two strips of cellophane; one red, the other blue. And as Castle charged in the prologue for the film, if you believed in ghosts, like he did, when the film changed hues, you were to look through the red filter, which allowed you to see the ghosts. But if you didn’t believe, or were a chicken, you were supposed to look through the blue filter, which filtered out all the ghosts. And at the end of the picture, if you still weren’t sure if you believed in what you saw, Castle encouraged you to take the ghost viewers home, where, when the sun goes down, and you were alone in your room, in the dark, you were supposed to look through the red filter again -- if you dared.

I’ve often wondered if Castle ever realized the biggest and best gimmick he ever had was himself? Apparently, Castle got the idea for Illusion-O while at the eye-doctor, where he had to look through several different lenses to see what prescription eye-wear he needed. It proved to be another hit as he barnstormed around the country, meeting up with his fan club members to help promote the film. Now, I had seen 13 Ghosts before, many times, but never in authentic Illusion-O until recently. To accomplish this, I took an old pair of anaglyph 3D glasses, with one blue lens and one red, and then just followed the instructions when prompted, using one eye or the other. The effect was quite startling. For while you can still see the ghosts without the aid of any filter, the red filter really makes them pop off the screen while the blue negated them completely. Thus, if you happen to have an old pair of 3D glasses lying around, just use them to look at the vidcaps and you'll see what I mean. And why the heck Columbia's otherwise excellent William Castle boxset didn't come with a viewfinder, especially when they included the tinted print, is beyond me.

And while Illusion-O definitely enhances the experience, I’m not sure if it was enough, or used enough in the film as Cyrus, after his ghastly encounter with the flame demon, which left a permanent scar, takes Dr. Zorba’s diary to his boss, Van Allen (Van Dreelen), which reveals the old kook created the X-Ray Specs as a magic viewfinder so he could tune-in and actually see the ghosts. (Whoa. Meta!) Further translating shows this was all in service to one of Zorba’s pet theories: if you could see the ghosts, you could capture and control them. And when this proved true, this ersatz ghostbuster traveled around the world, capturing himself an international menagerie of cantankerous spooks and cacophonous specters, and turned his mansion into an ectoplasmic petting zoo. Skipping to the end, the final entries state Dr. Zorba himself would be ghost number twelve. Now, this last bit befuddles Cyrus a bit because didn’t the Ouija board say there were thirteen ghosts currently loose in the house?

Speaking of ‘dem ghosts, Cyrus is called back home because one of those cranky poltergeists is currently running amok and making a mess of their kitchen. When Buck reveals this is Emilio -- a chef, who killed his whole family with a meat cleaver, don’t be getting any Sixth Sense vibes, here, because the kid doesn’t see dead people. No. He’s just been getting the full scoop from Elaine on who and what is haunting their house. Here, the plot unravels a bit as Cyrus and Hilda press the maid for more information. And even though Buck thinks she’s a witch, an accusation she neither confirms nor denies, rather hilariously, Elaine is very forthcoming, revealing she used to be Dr. Zorba’s assistant ghost-wrangler until the day he died.

Elaine also elaborates on how concerned she had been for Dr. Zorba as his time on this material plane expired. Not the ghost stuff, mind you -- that was normal for him, but the liquefying of all his assets, aside from the mansion, and the emptying of his bank accounts. This is what concerned her; and it all started after he first met Ben Rush. (Hrrmm? I wonder? Nah!) And then Dr. Zorba died under dubious circumstances, following another meeting with his new attorney. (Well that’s odd. Weird even. Maybe Rush … Nah, couldn’t be.) After the funeral, Elaine helped Rush search the house from top to bottom for the missing money but found nothing. And then this brief history lesson ends with a no B.S. warning to stay out of the master bedroom where Plato died; and frankly, the elder maid encourages Cyrus and Hilda to take their children and just leave this accursed house before it's too late.

But Cyrus, being the idiot he is, instead goes straight to Dr. Zorba’s bedroom (-- where he’s greeted by our old friend, the ominous wind, who really deserves a screen credit. I mean, c’mon, dude), where unseen hands and a free-floating candle shows how the bed was booby-trapped, revealing if a switch was turned, the bed's heavy canopy slowly lowers down and crushes the sleeping occupant, which, we’ll assume, is how Zorba met his demise.

Later, Rush and Medea return from a date. Again, Rush implores the girl to convince the others to leave because it’s just too dangerous to stay. (Geez, that guy really wants them out of there. I wonder why? Could it be that he's after? … Nah.) Saying it’s not up to her, Medea does promises to be careful as they say goodnight. But later that night, while she sleeps, Medea is assaulted by a ghastly ghostly figure, but it’s long gone when the other alerted family members come to see what all the screaming was about. (Wait! How could she see it without the X-Ray Specs? Ah! A clue! A clue! A clue!)

The next morning, Buck finds both the magic X-Ray Specs and Plato’s secret lab. Rummaging around, the boy finds the equipment of Shadrack the Great. Well, maybe not so great as the lion tamer wound up losing his head to one of his big cats. And when Buck puts the X-Ray Specs on, not only does he see the headless Shadrack but his lion as well. (And I freely admit I laughed myself into a hernia when the headless ghost looked into the lion’s mouth for his missing head and the lion was having none of it.)

Meantime, as he continues exploring the mansion, Buck also finds a sizeable wad of $100 bills that he unwittingly jarred loose from a hidey-hole while sliding down the banister. Just then, Rush shows up, sees the money, and wants to know where he found it. Since Buck isn’t sure where it came from, the lawyer swears him to secrecy, saying they will surprise the rest of the family with a huge windfall after they find the rest of Dr. Zorba’s treasure. (Okay, it’s pretty obvious now, but … Nah. It couldn’t be the Adam-12 guy, could it?)

Meanwhile, seems the attack on Medea has finally convinced Cyrus to finally move out of the house before someone really gets hurt. Glad to hear this, Rush promises through some legal finagling, he can probably get Cyrus and his family around $10,000 for the house. Just then, Allen blunders in rather excitedly; for he has translated another diary entry, which says Dr. Zorba hid all of his money somewhere inside the mansion. And since Rush already thoroughly searched the house, Cyrus hits upon a plan to hold a séance, with Elaine’s help, to contact Zorba and ask the spirit to reveal where the money is hidden.

Thus and so, Cyrus, Hilda, Medea and Elaine soon gather around the dining room table to start the séance. And while Hilda wouldn't allow Buck to participate, he decides to snoop on the proceedings anyway, sneaks out of his room, rides down the banister again, but jars the secret compartment completely open this time, which, upon closer inspection, is stuffed with Zorba’s fortune. Again, Rush arrives just in time to see all this and prevents Buck from spreading the good news, convincing the boy it will make a wonderful surprise in the morning before they leave the Zorba house and the ghosts for good. With that, proving gullibility is an inherited trait, Buck agrees to these terms and heads to bed.

Back at the séance, Dr. Zorba begins to channel himself through Cyrus. Speaking through his nephew, the decedent warns one of them -- that very night, will become the missing thirteenth ghost. (Or fourteenth ghost. Or whatever. Never mind, I think the movie's almost over.) So what do they do with this arcane knowledge from beyond the grave? Get the hell out of there before one of them ends up dead? Heck no! Not in this movie, Boils and Ghouls. Nope. Here, they all turn in for the evening; and, after he makes his customary bed check on his family, Cyrus is the last to hit the hay.

Meanwhile, in one of the most anti-climactic, "Well duh!", moments in cinematic history, the ghostly figure that attacked Medea is revealed to be Rush. (Route 66 guy, NO!) Collecting the sleeping Buck, he takes the boy into Zorba’s room, lays him on the booby-trapped bed, and then throws the switch, causing the heavy canopy to slowly lower down … down … down … and then down some more. Luckily, unlike his father, the ghost of Uncle Plato is on the ball (-- with an assist from the ominous wind. Hell, yeah! Blow, ominous wind, blow). And when this specter attacks Rush, Buck wakes up during the tussle, scrambles off the bed, and then watches as Dr. Zorba's ghost pushes Rush onto the deadly spot he just vacated. Buck screams, and then Rush screams, waking up the rest of the family, but it's too late for Rush as the bed crushes him flat.

Which leaves us with the denouement, where Cyrus, who has finally caught up with the rest of us, explains how Rush killed Zorba, and how he was trying to scare everybody off the property so he could find the hidden money. (Brilliant deduction there, Einstein. The rest of us figured that out over an hour ago.) Now completely loaded, Hilda still wants to move out and buy a newer house with the money, but Elaine assures the ghosts will no longer be a problem. With that, after the family gleefully goes into the kitchen for breakfast, Elaine smirks at the camera, the X-Ray Specs explode, and all thirteen ghosts noisily escort us out of the house, including the latest addition to this menagerie. (Hiya, Rush!) And when the door slams shut, a ghostly 'For Sale' sign appears on the door.

As the 1950s came to a close, Castle had been on one helluva roll with the publicity and box-office success of House on Haunted Hill and The Tingler. Somewhat sadly, his follow up feature, 13 Ghosts, feels a little too slapped and dashed to me and never reaches the true delirium of his earlier efforts. And I think the best way to explain it is how those other two mentioned films could survive on their own without the gimmick and still be entertaining, but I don’t even know if Vincent Price could’ve salvaged anything here outside of the Illusion-O interludes.

Somebody got their Richard Carlson mixed up with their Hugh Marlowe and begat Don Woods; a solid enough character actor for whom the script does no favors, here. (I have little patience for scripts or premises that require characters to be THAT stupid.) Same for Martin Milner, who might as well have been wearing a neon sign that flashed the words “Yup. I’m the bad guy.” Sadly, Rosemary De Camp doesn’t leave much of an impression, nor Jo Morrow except for her pipes when she makes with the lung butter. As for noted child actor, Charles Herbert -- probably best remembered as young Philippe in The Fly (1958), who found the other half of his father’s failed matter-transporting experiment trapped in a spider’s web for the climax, well, he only agreed to be in the film when Castle offered him top-billing, which rankled several of his older co-stars. Thus, the only real shining light in the cast was Margaret Hamilton, who was great, and whom the film should’ve exploited more in my opinion.

Now, one of the things that barely gets mentioned when discussing this film is the exterior location used for the establishing shots of Dr. Zorba’s mansion, which was none other than the Winchester Mystery House. Located in San Jose, California, the house was the residence of the late Sarah Winchester, widow of William Winchester, who created and mass-marketed the Winchester rifle. And as the legend goes, which served as the basis for the film, Winchester (2017), the widow feared the ghosts of everyone who was killed by her husband’s repeating rifle would come back to haunt her, resulting in an Escher-esque design to fool and trap these vengeful spirits. What we see in the film is not the main entrance, but one of the side entrances. Leave it to Castle to find an actual haunted house for his production.

The very same year of 13 Ghost’s release, Castle’s long time cinematic nemesis, Alfred Hitchcock, kinda had the last laugh on Castle, where he essentially aped the other director’s schtick and modus operandi with the low-budget shocker, Psycho (1960), which also had a gimmick where theaters were not allowed to admit audiences after the picture had started. Realizing his old fashioned monsters just weren’t gonna cut it anymore, in an effort to stay competitive, Castle struck back, and struck back soundly, with Homicidal (1961), which was his own take on transgender-induced psychopathy and murder, complete with its own gimmick: The Fright Break, which allowed audience members to take the coward’s walk and leave the theater before the movie ended.

But aside from the later Joan Crawford vehicle, Straight-Jacket (1964), and producing the bona fide classic, Rosemary’s Baby (1968) (-- a film the studio forbade him to direct, and a film I've never really warmed up to, which I blame mostly on my lifelong aversion to Mia Farrow, but those old Beelzefudds were an absolute hoot), Castle seemed to lose his way and kinda floundered around, trying to recapture the old magic. The problem was while he didn’t really change, his core audience had. All those card carrying members of his fan club grew up and got older.

And just like with George Pal in the early 1950s, Castle’s pictures always had a quaintness to them and were specifically geared toward children of a certain era between the ages of oh, say, eight to fourteen. But as they aged out of that bracket, the next generation, who had heard all about this guy and his films, probably took one look at his later efforts like Zotz (1962), The Old Dark House (1963), I Saw What You Did (1965) and Let's Kill Uncle (1966) and said, “Wait. What? That’s it?"

Don’t get me wrong, I love the old schlockmeister to death and I like most of his films -- even the non-gimmick ones, very much. Hell, some of them I even love. 13 Ghosts, however, is not one of them and is easily my least favorite. Again, one of the biggest problems with this film is it’s nothing without the gimmick, which was completely non-existent in the early home video releases, who skipped the tinted scenes and just released the whole thing as a composite in flat black and white, making the ghosts, well, ghosts of their former selves. This has been rectified in some later digital releases, of which I just watched, but not all. And if you can’t see the ghosts, well, what's the point and what chance does this film really have?

13 Ghosts (1960) William Castle Productions :: Columbia Pictures / P: William Castle / D: William Castle / W: Robb White / C: Joseph F. Biroc / E: Edwin H. Bryant / M: Von Dexter / S: Donald Woods, Charles Herbert, Jo Morrow, Martin Milner, Rosemary DeCamp, Margaret Hamilton, John Van Dreelen

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)