As an abused theremin is pushed to the limit and gets its eerie on something fierce, a taciturn narrator opines about what undiscovered mysteries are lurking in the vast, nigh impenetrable areas where man has yet to tread, which comes off as more of a warning than an invitation as we then zero in on a car parked near a heavily thicketed ravine near William’s Wash.

Here, in this secluded spot, Pat Wheeler and Liz Humphries (Vaughn, Salas) are happily engaged in what most young couples do alone in these secluded makeshift lover’s lanes. But then, this premarital necking is rudely interrupted when something rams into their car from behind. And as these two teenagers turn and look back, and then up, to gape at the culprit, the air is split by a behomothian roar as a huge clawed foot smashes down, knocking the car into the gulch. No apparent survivors.

This deadly development most likely explains why Pat and Liz failed to meet their friends later at Spook’s Malt Shop; the local hang-out for this group of teenage hot-rodders, led by the slightly older Chace Winstead (Sullivan), who’s just arrived with his girlfriend, Lisa (Simone). And after Chace fails to get the town drunk, Horace Harris (Fisher), to sell him his old ‘32 Model A so he can convert it into a souped-up deuce coupe, he tells Spook to relay to the now terminally late Pat and Liz to catch up with them at the drive-in as they all head out to catch the show.

Of course, Pat and Liz never show up for the double-feature, and then failed to return home, too, which is why Pat’s father, Mr. Wheeler (Thompson), a Texas oil man who carries a big stick in this county, summons the Sheriff (Graham) to his mansion, demanding to know why he hasn’t located his son yet. By now, Liz’s parents have reported her missing, too, and Wheeler fears his son has run off and eloped with some gold-digging hayseed. And in his frustration and disappointment, Wheeler starts redirecting his seething anger at Chace, scapegoating him as a hooligan ringleader and a bad influence on his son. But the Sheriff immediately comes to the boy’s defense, saying ever since his dad was killed on one of Wheeler’s drill rigs, Chace has been the sole supporter of his mother and younger sister by working full time as a mechanic at Compton's garage. So, if anything, Chace is a sterling example of responsibility to be emulated, not condemned. Unconvinced, Wheeler ends the conversation with a threat: find Pat or he’ll have his badge.

Thus, the search for the missing teens continues and the Sheriff’s first stop is Compton’s Garage, where he talks to Chace, who he is on very friendly terms with, to see if Pat and Liz were in any kind of “trouble” -- which is 1950s standards and practices speak for "was Liz knocked-up." Not that Chace was aware of, but Pat was a bit of a live-wire and the only one in their hot-rod club he could never rein in completely. He also offers Pat had nearly $500 socked away for a new engine. So they did have a nest egg if the couple were gonna elope, but Chace feels certain they would’ve said something.

Later, Compton (Hunt) returns with a special delivery: four quarts of nitroglycerin for Wheeler’s latest oil well-works and, lucky to be alive, gets an immediate lesson from Chace on the proper handling of the highly volatile liquid picked up from his late father. Once they’re safely secured, Chace then eavesdrops on a party-line with the Sheriff’s office he’d rigged up, looking to get a jump on any car accidents in need of a tow and hits pay-dirt: a wreck has been reported 12-miles outside of town on the highway that runs parallel to the dry riverbed that eventually forms William’s Wash.

Thus, Chace beats everyone to the scene in his hot-rod to hold off the competition while Compton follows in the much slower tow truck. When the Sheriff arrives next, he first gives Chace grief for not replacing his busted headlight as ordered two tickets ago before turning his attention to the car, whose front end is completely smashed in, as if it plowed into something, and the front seat is covered in blood. But there are no other signs of any occupants. And stranger still, the skid marks on the asphalt, which suggest the car didn’t careen out of control after hitting something but was instead seized as if by some giant hand and then pulled sideways into the ditch. As to what could’ve caused all of this? Well, between you and me, my money’s on the 30-foot long gila monster lurking in the brush down the road a piece, who is currently drawing a bead and appears ready to pounce on an unsuspecting hitchhiker...

As the legend goes, back in 1934 filmmaker John Ford arranged himself a commission as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Naval Reserves, and then started ordering himself to do his own personal reconnaissance missions on his sailboat down in Mexico, where he would track the movements of several Japanese fishing boats. And as global hostilities intensified, even before the United States officially entered World War II, Ford started recruiting others in the film industry for a proposed filmmaking unit that could provide covert photographic intelligence to aid in the impending war effort. Using costumes and prop weapons raided from the wardrobe department, Ford put his unsanctioned platoon through military drills on the sound-stages of 20th Century Fox. Included in this group were noted cinematographers Greg Toland and Joe August, editor Robert Parrish, screenwriters Sam Engle and Garson Kanin, and a young special effects artist and matte painter by the name of Edgar "Ray" Kellogg.

And while the Navy rejected this idea, Ford’s Field Photographic Branch eventually found a home in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, which eventually morphed into the CIA). Thus, what would affectionately become known as John Ford’s Navy would operate outside the normal military chain of command and reported directly to the OSS chief, “Wild” Bill Donovan. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, one of the Field Photo unit’s first missions, per Donovan’s request, was to make a documentary about the rebuilding of the decimated Pacific Fleet in order to reassure a nervous public of the Navy’s readiness and resolve, netting the docudrama, December 7th (1943).

Overseeing the wide-range of special effects needed for the re-enactment of this notorious surprise attack, Kellogg was in charge of the pyrotechnics, matte paintings, and miniature aircraft and navy ships as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was recreated in a large water tank at Fox studios. Kellogg would continue working with Ford throughout the war years. And when hostilities ended, he was assigned as a cameraman to cover the War Crime Trials at Nuremberg and, by most accounts, much of the familiar documented footage seen from the hearings were shot by Kellogg. After mustering out of the service, Kellogg went back to work for Fox as a matte painter and optical specialist, where he assisted the head of the department, Fred Sersen, in pulling off Gort’s deadly disintegrator beam in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1953), helped sink the unsinkable in Titanic (1953), and was instrumental in adapting standard special-effects techniques for the new wide-screen CinemaScope format.

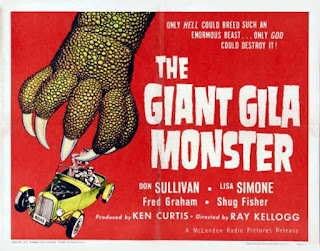

Then, after Sersen retired in 1952, Kellogg took over as head of the department and he would lead the FX team for the next five years, integrating mattes, miniatures, and live action elements in features ranging from Hell and High Water (1954), River of No Return (1954) and D-Day the Sixth of June (1956). But after handling the second unit direction on the miniatures and trick shots for Michael Curtiz’s The Egyptian (1954), Kellogg got an itch to direct; and so, ready to expand his cinematic horizons, he tendered his resignation in 1957, left Hollywood, and headed for Texas, where former Sons of the Pioneers crooner, Ken Curtis, and an eccentric drive-in theater chain owner by the name of Gordon McLendon were waiting to make a gonzo double-feature creature show: The Killer Shrews (1959) and The Giant Gila Monster (1959).

I’ve often suspected that Kellogg agreed to direct these two regional features to help secure the necessary union credentials needed to work in the same field back in Hollywood. Regardless of reason, his background in miniatures and FX work should’ve come in handy and been a boon to the productions but, speaking honestly, the worst part of both films are the janky execution of the titular monsters.

We’ve already covered the shortcomings of the shag-carpeted Killer Shrews a few years ago, but I will say the efforts of Ralph Hammeras and Wee Risser to bring the gargantuan gila monster to life do come off better than the monsters from its sister feature as a real life gila lookalike (and slightly less temperamental) Mexican beaded lizard is coaxed and prodded through several spiffy miniature sets. However, the budget just wasn’t there to matte anything together or combine any rear-projection shots, meaning there is no direct interaction between the gila monster or its victims, whose attacks are accomplished by a jumble of edits of reaction shots, dutch angles, voice-overs, suspension of disbelief, and close-ups of the lizard sticking its tongue out at the audience, exemplified by the death of the anonymous hitchhiker.

Beyond that, it’s mostly up to Jack Marshall’s theremin heavy score to announce the gila monster is present and lurking somewhere nearby as Chace and the Sheriff finish up at the wreck, with the Sheriff allowing the always cash-strapped Chace to pilfer some needed parts (headlights and tires) from what turns out to be a stolen and now totaled vehicle. On the way back into town, they find the abandoned suitcase of the now long masticated and partially digested hitchhiker, and figure it might tie in with whoever stole the car.

Luckily, the next person to have a close encounter with the gila monster survives when it darts across the highway, running another car off the road. But when the highly intoxicated driver tells Chace he saw something big and black with pink stripes blocking the road, he assumes it’s just the booze talking, tows the Caddy back to the shop, and starts the repairs while his customer sleeps it off. Here, Chace happily sings as he takes a hammer to the damaged fender, beating it back into shape. This noise finally arouses the drunk, who introduces himself as Horatio “Steamroller” Smith, a local disc jockey. Seems the Steamroller liked what he heard from Chace, singing wise, leaves a business card and an open invitation to come and see him in the city to talk business, and then caps this interlude by paying his Good Samaritan savior two $20s for a three dollar bill.

As Chace Winstead, actor Don Sullivan plays another affable, stand-up guy in a long line of affable, stand-up guys in a short but memorable string of B-movies. Born in Salt Lake City, Utah, but raised mostly in Idaho, after a stint in the Marines, Sullivan then earned a degree in chemistry at the University of Idaho through the G.I. Bill. And then, with three dollars in his pocket and a passing resemblance to a young Clint Eastwood, Sullivan headed to Hollywood to find fame and fortune.

There, he started dating actress Judi Meredith -- Jack the Giant Killer (1963), Queen of Blood (1966), and enrolled in her acting classes, where he was discovered by Hugo Haas, who gave him the romantic lead in Paradise Alley (1958). Steady work on TV followed before he wound up as the hero in a trio of micro-budgeted, whirlwind monster movies -- The Giant Gila Monster, The Monster of Piedras Blancas (1959) and Teenage Zombies (1960), and a beatnik bandit in The Rebel Set (1958). But just as his acting career seemed to be gaining some traction, after a prolonged two-punch actors and writers guild strike that lasted nearly half a year, Sullivan officially retired as an actor, falling back on his degree, which led to a highly successful career in cosmetics.

Sullivan also fancied himself a crooner, and while his voice is passable his songwriter skills aren’t so hot according to the three original songs he wrote and performed in The Giant Gila Monster -- the nonsensical "My Baby, She Rocks", the insipidly folksy “The Mushroom Song”, which we get to hear performed not once, but twice, with ukulele accompaniment not once, but twice, and finally, the almost catchy "I Ain't Made That Way", which, of course, we only get to hear about half of. And like with Ingrid Goude in The Killer Shrews, Sullivan’s co-star was another Miss Universe contestant, this time from France. And to explain away Lisa Simone’s accent, screenwriter Jay Simms added some drama by making her a ward of the tyrannical Mr. Wheeler, who would blow a gasket and have her deported if he ever found out that Lisa was dating Chace, especially now with his son missing.

So, they do their best to keep their relationship on the sly until Chace can fix her visa problem. And Lisa is with Chace when he and a couple of other teens volunteer to help the Sheriff search the miles of back-roads and dense thicket around Williams Wash, where, as the gila monster prowls around, they eventually find Pat’s car overturned at the bottom of a ravine.

But with no sign of the occupants, instead of waiting for the Sheriff, Chace and the others recover the wreck and haul it back to the garage before the scene can be properly investigated. Later, as Compton drives a truck loaded with fuel oil down the highway, the monster strikes again, knocking the vehicle into the ditch, where it detonates on impact.

Meantime, when Chace returns home he finds Lisa there waiting for him with his family. Seems she spent part of her salary on a pair of leg braces for Missy, Chace’s little sister, who is battling polio. Here, Missy (Stone) tries to use them to walk over to her brother unassisted. And though she doesn’t quite make it, Chace is very proud of her and rewards the girl with a couple of verses from “The Mushroom Song.” But this is interrupted by a call from the Sheriff, who breaks the news to Chace about Compton.

Racing to the scene, the wreck is still burning but they can find no trace of the driver. On the highway, the same tell-tale skid-marks. Here, the Sheriff starts connecting the dots between these accidents and reports of odd livestock thefts -- one cow at a time, here and there, but it’s starting to add up to something sinister.

The following morning while Chace is in town on “business,” Steamroller Smith announces over the air that he will be hosting the local platter party at Hargartay’s barn as a favor to his new found friend. (For those not hip, a platter party means spinning some records and dancing, hepcats.)

Meanwhile, the ever-drunk Harris is puttering along in his Model-A until he spots an oncoming train, floors it, and barely makes it over the crossing before the engine roars past. Further up the tracks, the gila monster is also puttering along, but it’s over the clearance rate as it moves underneath a trestle, destroying it. And when the train derails and crashes as it runs off the mangled tracks, as the passengers scream in terror, the gila monster crawls all over the wrecked cars, looking for any tasty morsels.

Meantime, after dropping off Missy at the Blackwells for a slumber party, Chace stops by the Sheriff's office on his way to the barn dance. Seems the Sheriff has been consulting with a zoologist over the phone on how a change in diet can cause dwarfism and gigantism in some animals; like those giant skeletons scientists recently unearthed, who traced it back to certain salts washing down into the delta, which then worked its way into the food chain. He also reveals both Harris and several survivors of the train wreck swear a giant gila monster caused it.

Here, Chace remembers what Smith described crossing the highway: a giant with pink stripes, and realizes it must be real. This, of course, means in all likelihood, Pat, Liz and Mr. Compton are all dead. With that, the Sheriff charges Chace to both keep this under his hat and to keep all the kids safely inside the barn until he can round up some help to flush the monster out and, hopefully, destroy it. But the Sheriff takes this news to Wheeler first, who already heard about the attack on the train. Accepting his son is most likely dead, he once again redirects his anger and grief on Chace, and wants him arrested for tampering with evidence for moving Pat’s car, and theft, for stealing parts from all the wrecks for his own needs (-- with the Sheriff’s permission). And knowing the Sheriff is soft on the boy, Wheeler will accompany him to see this arrest through.

Meanwhile, at the barn hootenanny, Steamroller Smith treats his audience to a brand new demo record and offers a reward to anyone who can identify the singer. And after several rotations of "I Ain't Made That Way" Lisa can’t hold it in any longer and tells the stumped listeners it’s Chace singing on the record, who spent the morning laying the track (-- and who blew part of his signing bonus on a new paint job for his car). Thankfully, before he gets to a third verse of “The Mushroom Song” to appease his new found fans again, AGAIN, the Sheriff and Wheeler arrive, bringing the party to an abrupt end.

However, before Chace can be arrested, the gila monster strikes, smashing its way into the barn. But everyone escapes unharmed (-- there’s a long rumored cut scene where a drunk Harris is caught and killed while fleeing up into the loft instead of outside, and you can see him heading up the stairs when the crap hits the fan), and the Sheriff manages to drive the monster away with his shotgun.

Needing more firepower, the Sheriff deputizes Wheeler and orders him to keep the kids corralled up and safe while he goes and rounds up some State Troopers. Once he’s gone, Chace gets an idea on how to stop the gila monster; so he and Lisa speed to the gas station, where they carefully load up his car with the nitroglycerin.

Following the gila monster’s trail of destruction to the Blackwell house, a distraught Chace searches the debris for Missy but there’s no sign of anyone. Screams from behind the house brings Chace, the car, and the nitro a'humming cross country, where Lisa tries to hold the canisters steady as they bump along the terrain. They catch up with Missy and the Blackwells, and Chace orders Lisa to get out and hold Missy low to the ground.

Once she’s clear, he floors it and heads right for the pursuing lizard. And while Chace loses this game of chicken by bailing out before his car hits his target, the giant gila monster loses the war as the nitro explodes, ending its reign of terror for good.

In an interview with the LA Times around 1984, Gordon McLendon said, “A lot of people say [The Killer Shrews] was the worst movie ever made, and I always say that is not true. I have made two films worse than that.” I have a feeling the set-up for that punchline might be interchangeable, depending on which film they were asking about.

One of those well-diversified Texas tycoons, McLendon made most of his money in oil and real estate before expanding into TV and radio, owning and operating the Liberty Broadcast Network, which had stations in Dallas, San Francisco and Tijuana, Mexico, which were instrumental in the propagation of Rock ‘n’ Roll and set the template for what was to become the Top 40 survey. Then, in the 1950s, he expanded his media empire further by forming a new theater chain, opening a bunch of drive-ins in Texas. And like a lot of theater owners back then, McLendon decided to finance and produce his own double-bill to get all of the box-office pie.

Recruiting talent from Hollywood behind and in front of the camera, right before he signed on to play Festus in the TV-series Gunsmoke, Ken Curtis agreed to produce The Killer Shrews and The Giant Gila Monster for McLendon’s newly formed Hollywood Pictures Corporation, which was actually based out of Dallas, Texas. Both films were shot there, too, using one of McLendon’s TV stations as an impromptu studio. Curtis would also star in The Killer Shrews, as would McLendon, who would also serve as narrator in both films. Meantime, McLendon’s wife, Gay, would have a bit part in The Giant Gila Monster playing Chace’s mother, and his father, B.R. McLendon would serve as a co-producer. Ken Knox, who played Steamroller Smith, was an actual disc jockey working at one of McLendon’s radio stations. And fellow former Sons of the Pioneers Shug Fisher does well as the besotted and not as odious as it could’ve been comedy relief.

But none do better than Fred Graham as the Sheriff. A former stuntman and henchmen in many a matinee serial, Graham brings some definite weight and really grounds the movie. I really like the relationship he has with Sullivan’s character, where he almost comes off as a surrogate father figure. There’s a trust there that’s been long earned in events that happened well before the giant lizard started eating people. And one of the craziest things about The Giant Gila Monster is just how pro-teenager it is given the time and tenor of it’s release. Sure, other films showcased teenagers sticking it to their elders over the ever-widening generation gap but this film is with it, man, right down to the marrow. I dug how honest it was about Pat and Liz’s disappearance that went well beyond any riffs on “Wake Up, Little Suzie,” and the Sheriff got right to it, wanting to know if Pat had knocked the girl up.

It’s no surprise given McClendon’s background in radio that this movie would also be pro Rock ‘n’ Roll. Sure, Chace’s tunes were pretty lame but there wasn’t that much margin for error. Remember, at the time, Rock ‘n’ Roll music was being clinically described as "cannibalistic and tribalistic," that "appeals to the base in man, which brings out animalism and vulgarity" and encouraged wanton rebellion and miscegenation. And then The Giant Gila Monster doubles-down and takes it one step further by openly embracing the burgeoning custom car culture, too, which is currently thriving on screen under self-regulation. (And I’m pretty sure Old Man Harris would have a heart attack if he saw what his Model-A would bring him in today’s kustomizing market.)

And kookiest of all, in other teen films of this vintage, a compromise is usually reached with the established authority. But here, epitomized by that malicious jack-ass Wheeler, the authority is clearly in the wrong and, in the end, it is Chace’s nemesis that sees the errors of his ways, offering to replace his car and gives him a job for his selfless actions. And if the film makes any kind of mistake, and it’s nearly fatal, is the script calls on Chace to be virtuous to the point of ridiculousness.

Which I guess brings us to the 20-ton giant gila monster in the room. For, yes, it is the special-defects that prevents The Giant Gila Monster from reaching full bloom. I honestly think some of those process shots really could’ve shored things up considerably. I have jotted down in my notes that Kellogg brought the film in under budget but I’m damned if I can find the source. Multiple sources report both features were budgeted around $175,000 a piece and the figure I had for Gila Monster was $138,000. So maybe some extra FX work was intended but they ran out of time and just let it go as is? Also, I think the film blew a golden opportunity by not finding any bodies. The gila monster is a rare venomous lizard after all, and finding gallons of poison in the mangled corpses would’ve only added another twist to the unraveling mystery.

Of course, the double-bill of The Killer Shrews and The Giant Gila Monster were only supposed to play regionally in McLendon’s theaters down south but proved viable enough they were picked up by American International and released nationally in late 1959. And when you consider the budget to box-office ratio, these films were considered the most successful regionally produced films until they were dethroned almost a decade later by Night of the Living Dead (1968).

Putting McLendon’s self-deprecating comments aside on the quality of his film catalog, I find it kinda disappointing he only made a grand total of four films -- these two, an immediate follow-up family friendly feature, My Dog Buddy (1960), which I feel is the worst of the lot, and then he returned as an executive producer in 1981, working with Lorimar and Paramount on the notorious star-studded flop, Victory (1981). Undaunted, McLendon was ready to get back into the business full swing, and was in the process of putting a budget together for his next feature when he unexpectedly passed away in 1986.

As for Kellogg, after directing My Dog Buddy, he returned to Hollywood, working as one of many second unit directors on the boondoggle to end all boondoggles, Cleopatra (1963), as well as Batman: The Movie (1968); and, after directing John Wayne in The Green Berets (1968), Kellogg wound up right back where he started, recreating the Battle of Pearl Harbor again in Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970).

And as we wrap this up, two things. One, if you can track it down, I highly recommend Les Simons novel, Gila!, where a whole herd of giant gila monsters invade New Mexico and go on a rampage for the ages. And two, I want to be perfectly clear that I love both halves of Kellogg's kooky double-bill. I think Variety summed it up best back in 1959: “As a horror film it’s quite good given the economics involved.” And like with The Killer Shrews, I believe Kellogg managed to overachieve beyond those budgetary limitations on The Giant Gila Monster, too. The films’ titles said it all, along with some amazing poster art, and what was said was actually delivered. A minor miracle that should be celebrated, and not derided.

What is Hubrisween? This is Hubrisween! 26 Days! 26 Films! 26 Reviews! And now, Boils and Ghouls, be sure to follow this linkage as The Fiasco Brothers and Yours Truly countdown from A to Z all October long! That's seven reviews down with 19 more to go! Up Next: All aboard the terror train! No, not that one. The other one!

The Giant Gila Monster (1959) Hollywood Pictures Corporation :: McLendon-Radio Pictures Distributing Company :: American International Pictures / EP: Gordon McLendon / P: Ken Curtis, B.R. McLendon / D: Ray Kellogg / W: Jay Simms / C: Wilfred M. Cline / M: Jack Marshall / S: Don Sullivan, Fred Graham, Lisa Simone, Ken Knox, Janice Stone

No comments:

Post a Comment