Somewhere along a lonely stretch of road, way down south of the Mason-Dixon line, a couple of surly bumpkins by the name of Rufus and Lester monitor the passing traffic. And whenever they spy a car bearing a plate from a northern State, Rufus (Bakeman) signals Lester (Moore), who sets up what looks more like a trap than a dubious detour that eventually leads two cars and six hijacked Yankee tourists into the bucolic town of Pleasant Valley, population: 2000, where all signs on main street point to some kind of centennial celebration (1865-1965) is currently underway.

But if you look a little closer behind all those smiling faces and waving Confederate flags at the nooses everyone seems to be carrying around -- that the young folks have been liberally using to strangle cats and other critters, you probably would, and should, conclude something sinister is going on here despite the jubilant crowd gathering around these outsiders.

Thus, at first thinking they’re in some kind of trouble or are under arrest, the Mayor of Pleasant Valley, Joseph Buckman (Allen), steps forward and welcomes these visitors as special guests of honor for the centennial, where they’ll be treated like royalty over the next two days, with free room and board, a heapin’ helpin’ of Southern Hospitality, and then serve as vital participants in the celebration to come.

A bit overwhelmed while taking this all in, we have a pair of married couples in the first shanghaied car: David and Beverly Wells (Korb, Gilbert), and their bickering friends, John and Bea Miller (Eden, Livingston). Behind them in the second car we have Teri Adams (Mason) behind the wheel, a Good Samaritan, who gave Tom White (Kerwin) a lift when his car broke down on the way to a teacher’s convention in Augusta, Georgia.

Thus and so, with places to be, Tom is flattered but tries to beg he and Teri off. But Buckman and the others won’t take no for an answer and escorts these V.I.P.s to the hotel, saying they won’t regret this and their decision to stay will ultimately result in something truly special that they will remember for as long as they live -- he typed ominously.

Now, the first item on the list of these festivities is a barbecue scheduled for later that night. And once the visitors are safely ensconced in the hotel, Buckman not-so-secretly conspires with Rufus and Lester to draw one of them back out alone -- specifically the big blonde, Bea Miller. Thus, they set a plan of divide and conquer into motion, siccing the busty Betsy (Cochran) on the surly husband and the hunky hayseed Harper (Douglas) on the harpish Bea. And once they’re alone in the woods and passions start to boil over, Bea worries they won’t be back in time for the barbecue; but Harper says not to worry, insisting that, without her, there will be no barbecue.

With that, Harper produces a knife and proudly coaxes Bea into testing how sharp it is by running her thumb across the tip. When the wary woman complies, Harper not so clumsily slips and slices her thumb open. And as Bea loses her mind at the small amount of blood, the man tries to calm her down, saying he can fix it. And when I say “fix it,” I mean chop-off her thumb entirely!

Passing this off as an accident, Harper hauls the hysterical woman to Buckman’s office, claiming he’s also the town doctor. But once there, Bea is thrown across his desk and restrained by Harper, Rufus and Buckman while Lester gathers an axe and starts dismembering her while she’s still alive! And when this ghastly scene concludes, we realize two things: one, a similar bloody fate is most likely in store for all those other unwitting gathered guests of honor; and two, since Bea was a “pivotal ingredient” we also probably know what’s on the menu for tonight’s barbecue...

Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol first opened its doors back in 1897. At the time the smallest venue in Paris, the converted chapel with its Gothic trappings, stone angels lurking over the orchestra pit, and box-seat confessionals had the air of something blasphemous about it before the curtains were even drawn back.

And then things got even more eerie -- and grisly, in 1898 when Max Maurey took over as director, who shifted the focus to the macabre and the horrific, where they judged how successful a performance was by how many faintings there were reported in the audience each night.

See, on a nightly basis in the Grand-Guignol, audiences witnessed stabbings, dismemberment, and all kinds of fiendish torture, which came off as so realistic people started vomiting in the aisles before they fainted. Of course, it was nothing but conjurer’s tricks, sleight of hand, and copious amounts of grue borrowed from the butchers and a ton of fake blood.

Since the beginning, the formula for the stage blood used at the Grand-Guignol was a closely guarded secret, which was less a concern about the competition horning in and more about shattering the illusion of what was being seen on stage. For the blood itself was nothing more than a 50/50 solution of Carmine and glycerin.

Carmine was a dye of bright red pigment made from boiling the dried husks of Cochineal beetles, while glycerin is a colorless, odorless and viscous liquid base that made the faux blood glisten under the lights. And when the time to deploy the blood on stage was imminent, if you listened closely, you might’ve heard someone backstage whisper, “Vite, réchauffer le sang” (-- Quickly, heat the blood), which thinned the mixture and let it flow and splatter more freely and realistically. It was all part of the show, and the show, clearly, was all about the blood.

And blood -- well, fake blood, was also on director Herschell Gordon Lewis’s mind, too, in the run-up to filming Blood Feast (1963). Before then, Lewis and his partner, former carnival huckster Dave Friedman, had been making a string of bawdy Adult Films and Nudie-Cuties -- Living Venus (1961), The Adventures of Lucky Pierre (1961), Goldilocks and the Three Bares (1963), out of Chicago and filmed in Florida, but with the Nudies devolving into Roughies, along with increased competition and decreasing box-office receipts on the skin flicks, it was clear they needed to find another new, profitable niche to exploit. Something the majors couldn’t do, and something no one else had tackled yet that people might pay to see. And the answer was simple: gore.

In later interviews when talking about the genesis of Blood Feast, which would coronate him as the Godfather of Gore, Lewis recalled watching some old gangster movie on TV, where the star, Edward G. Robinson, is gunned down in a hail of bullets during the climax. “He died quietly,” said Lewis, with a little splotch of blood on his shirt. “And I said, Waitaminute! That isn’t right.” Right there, with that kind of sugar-coating, it was clear to Lewis that he could do the same thing only a lot more realistically and gruesomely in his independent features. And more importantly, he could do it more viscerally, to really knock ticket-buyers onto their unsuspecting cans.

Of course, since the early days of Hollywood blood was literally sugar-coated, with Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup or Bosco’s Milk Amplifier subbing in for what little blood got past the censors, whose darker brown color added more contrast on screen than any red dye could in those old black and white films -- and it was still in use for the likes of Psycho (1960) and later in Night of the Living Dead (1968).

But with the switch to color film stock, while chocolate was out the blood would remain sugar-based as the main ingredient was corn syrup and red food dye. But the new cinematic standard for fake blood was the copious amounts of “Kensington Gore” employed by Hammer Studios in their Technicolor Gothic romps, beginning with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and The Horror of Dracula (1958).

This formula was perfected by John Tinegate, a retired British pharmacist, who mixed corn syrup, warm water, a ratio of red and blue food coloring, then corn starch to give it some viscosity, and a dab of mint for taste if a character was called on to bleed from the mouth. And perhaps in a concession to the censors to make it less realistic, the blood that flowed so freely in Hammer’s horror films was cartoonishly bright red instead of a darker crimson.

Meantime, in Hollywood, Max Factor had cornered the faux blood market, essentially using the same formula. It was also very expensive for what little came in the container and it didn’t have much of a shelf-life. And for what Lewis and Friedman had in mind for Blood Feast, where a cannibalistic caterer goes on an eviscerating rampage through south Florida, they were going to need gallons of the stuff. Also, after a few tests, Lewis didn’t like how the cosmetic blood showed on screen, which he felt looked fake and gave off a purplish hue.

And so, Lewis started experimenting. And with an assist from Barfred Laboratories, a cosmetics company based out of Coral Gables, Florida, where Blood Feast was shot, after a few false starts, they concocted a brand new formula that hewed a little closer to the proper color, opacity and consistency of real blood -- and best of all, it came in at only $7.50 per gallon.

Now, aside from a mix of food-coloring, the main ingredient of this new formula was the over the counter diarrhea remedy, Kaopectate, which served as the base. This was important because the blood still needed to be non-toxic and edible for some of the gags Lewis and Friedman wanted to pull off in the film -- most notably the notorious tongue removal scene. And the only real mistake Lewis made in this scientific endeavor is he failed to patent the formula as Barfred Labs started mass-marketing the product to other filmmakers.

Truth told, as a film, Blood Feast is just terrible. (Lewis later insisted the film wasn’t made, but excreted -- shat out.) There was no script to speak of, the acting is uniformly awful, and the primitive cinematography was nothing short of point and shoot and pray. But as an exercise in the grand guignol tradition, it is completely bonkers and something to behold as Lewis mixed his new stage blood with some strawberry preserves, minced cranberries, and a lamb’s tongue borrowed from a local slaughterhouse and stuffed it down one of his actress’s mouth only to be removed again on film. It was unique, it was awful, and there was nothing else like it.

As they were editing the film together, neither Lewis or Friedman had any idea of what they had or if it would play. To test the waters, they opened Blood Feast at a small Drive-In in Peoria, Illinois. It opened on a Friday, and on Saturday, Lewis and Friedman hopped in a car to go and see how audiences were reacting to it. But they never got the chance. Caught in a huge traffic-jam several miles from the theater, Lewis asked a State Trooper directing traffic if there’d been an accident. Told it was over some cockamamie horror movie, and the line to get into the Peoria Drive-In ended here, the filmmakers knew they had struck a nerve and had really tapped into something. And right then and there, before the money from Blood Feast even started rolling in -- and it did, hand over fist, Lewis and Friedman knew they needed to follow it up with something in the same grisly and graphic vein.

The problem was, How do you follow up on something like Blood Feast? For you can only surprise an audience once with a film like that. And with that kind of shocking success, expectations start to rise. To compensate for this, Lewis was determined to make a better and more polished film. For if Blood Feast was making that kind of money, imagine how much it would’ve made if the movie was actually any good?

As for the story they would tell, inspiration came when Friedman and his wife caught a revival of the Lerner and Loewe Broadway Musical, Brigadoon, which tells the tale of two American tourists lost in the highlands of Scotland, who stumble upon the mythical titular village which only appears for one day every 100 years. And during their limited stay, one of these tourists falls madly in love with one of the local girls. And while the musical and the later movie adaptation of Brigadoon (1954) focused on the doomed romance and a pat happy ending, Lewis took that nugget of an idea of a phantom town and turned it into something truly twisted.

A true auteur, Lewis served as producer, director, screenwriter, cinematographer, editor, and scored nearly all of his own films in some capacity. His first feature was The Prime Time (1959), and his first co-production with Friedman was Living Venus, which was loosely based on the life and times of Hugh Hefner leading up to his publication of Playboy Magazine. But before he started making commercials and, later, feature films, Lewis had taught several semesters of journalism and communications at Mississippi State University.

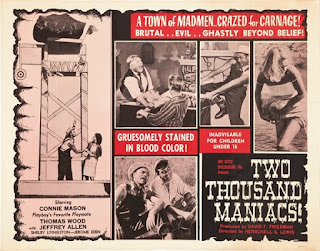

Immersed in southern culture, which he claimed to love, especially the old-timey music, and well versed in the grudge some southern States still held over losing the “War of Northern Aggression,” Lewis tapped into these hard feelings for what was to become Two Thousand Maniacs (1964). Moving the phantom village from Scotland to the postbellum south, the catalyst for the reappearance was 100 years ago, as the Civil War drew to a close, a band of renegade Union soldiers invaded the town of Pleasant Valley and massacred all 2000 of its citizens.

And now, 100 years later, the town and townsfolk have reappeared and seek revenge on six unwitting northern tourists they lured in to participate in their celebration -- not realizing they were dealing with rancorous phantoms, and this celebration they’ve been suckered into rests solely on their own imminent demise.

Why only six victims? Well, the script nor the movie ever get around to explaining that magic number. But six it is -- well, five now, as the barbecue gets underway. And by the time the guests of honor arrive, the meat on the spit has been so charred it’s source is unrecognizable. Not that it matters, as the naive David and Beverly Wells are pretty oblivious, and Betsy has got Johnny Miller so blitzed out of his gourd on corn-liquor he doesn’t really care that his wife has disappeared, while Teri Adams is preoccupied with wondering what Tom White has been up to all day.

Suspicious of everyone and everything from the jump, it seems Tom has spent the day nosing around on his own, trying to discover the real reason these too insistent and all too friendly people would go out of their way to rope in a bunch of outsiders, intruders, really, for a local celebration such as this. And while all efforts to reach anyone outside of town are thwarted through subterfuge, Tom has managed to finally find some sinister proof and manages to sneak Teri away from the festivities to show her the old Civil War era memorial plaque he found:

And it’s the sentiment of that last bit that has Tom convinced he, Teri and the others are in mortal danger and will be killed as a sacrifice to atone for those slaughtered in the Pleasant Valley Massacre back in 1865. But this realization comes too late for the inebriated Johnny, who lingers around as the barbecue breaks up and the Wellses are escorted back to the hotel. Alone with the locals, Johnny is asked to partake in a “Horse Race.” Alas, Johnny is too drunk to realize what is happening as he is lashed to four horses to be drawn and quartered. But I’m pretty sure it finally sank in when his limbs started snapping off.

And like in the aftermath of Bea’s murder, in a strange twist, there is a lingering moment of sober reflection by those gathered around over what they’ve done. Maybe even some guilt or regret over the innocent lives taken. Here, Lester doesn’t even need to spell out the dire consequences of what will happen to anyone who tries to back out; the threat is enough to snap the townsfolk out of their funk. And then a few rousing verses of “Dixie” gets everyone’s blood back up to finish what needs be done come sun up.

And so, the next morning, knowing they’ve almost blown it, Buckman and the others station a guard to watch Tom and Teri’s hotel rooms, which keeps them from snooping around any further and also prevents them from warning the others of their suspicions. And while Beverly is off on a walking tour, David is taken to the top of a steep hill, where he’s coerced into participating in the Barrel Roll. And while that may sound innocent enough, once the man is straddled through the barrel, Buckman starts pounding some sizeable nails through the wood.

And once the spike-embedded barrel is kicked down the hill with the man still inside it, reaches the bottom, and shatters, David has been turned into a veritable postmortem pin-cushion.

Meanwhile, back at the hotel, Tom and Teri manage to overpower their guard and escape. With Harper in hot pursuit, they flee into a marsh. And while the couple is able to avoid the quicksand, their pursuer does not and Harper sinks to his doom.

Elsewhere, Beverly’s walking tour ends at Teetering Rock -- a huge boulder sitting precariously on top of a high wooden scaffolding. And as the guest of honor, Beverly must judge the exact moment when the rock will fall. And to do that, she will need the proper vantage point of lying down directly below the infernal thing. Of course, the woman does not do this voluntarily as the others tie her down to the platform.

Here, the insidious nature of this set-up finally comes into focus as it becomes clear this whole thing is like some giant ersatz dunk-tank, where the locals take turns throwing a ball at a target. And if they score a bullseye, the rock will fall and crush Beverly. It took a grand total of four tries before Rufus finally finds the mark, the rock falls, Beverly goes squish, and then the flattened corpse joins her husband’s at the bottom of a nearby pond.

With only two victims yet to go to complete the blood pact, Buckman and the others can’t wait to get Tom into the “Axe Throwing Contest” and have that pretty little filly Teri run “The Gauntlet.” But then word comes they’ve escaped custody and are on the loose. And as Lester and Rufus round up a posse to catch them, Tom and Teri are doing their best to stay out of sight while trying to track down Teri’s car. They run into some luck when they manage to bribe a young boy named Billy (Santo) with a promise of a trunk full of candy if he shows them where the car is hidden, and then kick him to the curb once the little shit-stain’s usefulness comes to an end.

Thus, through guile and grit and the skin of their teeth, Tom and Teri escape and make it back to the main highway, leaving the pursuing horde of rednecks and hayseeds and their ramshackle truck in the dust. Not to worry, says Mayor Buckman, as he orders everyone to clean things up and take all the banners down. Four out of six is the best they’re gonna do this round, and he assures all no one will ever believe the story of what really happened by those who got away.

And Buckman’s words prove prophetic when the Sheriff in the next town forces both Tom and Teri to pass a field sobriety test after listening to their tale of multiple maniacs and blood sacrifices. Seems he’s never even heard of a town called Pleasant Valley, but when they prove sober and sincere, he agrees to at least check out the area where they say the town is. But when they arrive at the fork in the road, all traces of the town are gone. Here, the Sheriff (Wilson) finally recalls an old legend about a town that was razed by renegade Union troops during the Civil War, and how the ghosts of the victims still haunt the area, allegedly, vowing to one day return and seek vengeance. Allegedly.

Whatever the truth may be, Tom and Teri have experienced enough over the last few days; and in a scene that would be later echoed at the end of John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972), the Sheriff encourages these two to just leave and to never, ever come back here. And as the newly minted couple does just that and never looks back, knowing full well these ghostly events actually happened with Billy’s noose found in the backseat as proof, Rufus and Lester watch them go, and then start conjecturing on what it will be like during the next centennial in 2065, and how they might have to detour some rocket-ships into Pleasant Valley. And as they turn to leave, they call for Harper, who emerges from the bog and joins them as they disappear into the fog enshrouded forests.

On all fronts, Two Thousand Maniacs was a vast improvement over Blood Feast. The budget was triple the amount of what was expended on the first feature and it definitely shows from a technical standpoint as Lewis appears a lot more assured with some clever set-ups and a lot more coverage. It was definitely more restrained, too, metering out the gore strategically instead of just carpet-bombing the whole damned picture.

I think my favorite bit was with the Teetering Rock. I love the touch of all the dirt on top of the Styrofoam boulder to give it some weight when it finally falls. And the cutting around the impact, with only a brief glimpse of Beverly vomiting up blood and how this enhances the splat as the imagination takes over from there. Lewis also injected a lot more gallows humor that made it all the more palatable. And swear to god, this movie could, and should, actually be considered a musical with the constant presence of its roving, banjo-strumming minstrels. And that’s Lewis singing and yee-hawing the notorious theme song, “The South’s Gonna Rise Again."

Now, the plot the music and the gore is plugged into also makes a lot more sense, though if you think about the mechanics of it too hard the holes start to show and it starts leaking both fast and furiously. See, one of the things Lewis failed to port over from Brigadoon was the fact the Scottish village that magically appears in the musical was a rustic time capsule of a bygone age, while Pleasant Valley is a contemporary southern town of 1964 and its denizens act accordingly. This, does not compute. This also wasn’t Brigadoon’s first reappearance (-- if I’m remembering the movie version right), while it was the inaugural resurrection of its surrogate according to the film’s lore.

When first encountered, when I was finally brave enough to rent Two Thousand Maniacs back in the day because I found the covers of both VHS versions to be slightly unsettling -- the Video Kingdom had the Comet Video version, and the Applause Video had the Force Video tape, and I believe I finally went with the Force version, I honestly thought the townsfolk were cannibals, possessed by the ghosts of their ancestors to carry out these blood sacrifices every 100 years. (Also, in this instance, 100 years seems awful arbitrary.)

To me, this makes a helluva lot more sense than Buckman and the others being the ghosts of the original victims, for how would they, after reappearing from a 100 year absence, know what a car is, or a telephone, or running water for that matter? Anachronisms can sure be a bitch in a tale like this. And there are several other interesting ideas that Lewis and Friedman kinda left to die on the vine to make the Brigadoon riff work. I would’ve loved some expansion on the initial grim reactions once each bloody deed is done. Maybe show us what would happen if someone did refuse to participate? It could still work if you have the ghosts of the dead rise when Buckman and the others fail to complete their task, consume the town, and wipe it off the map. Then again, Why would anyone want to think about Two Thousand Maniacs too hard? Right? Right.

The cast was also an upgrade, even though the two main players, Bill Kerwin and Connie Mason, were holdovers from Blood Feast. Mason wasn’t much of an actress, who got the initial role so Friedman could exploit the fact she was a Playboy Playmate. In the interim, Mason had been upgraded to a Playmate of the Year, allowing Friedman to talk a reluctant Lewis into using her one last time.

To be fair, Mason appears a lot more comfortable this go round, even though she apparently couldn’t remember her lines worth a damn and half of them wound up going to Kerwin -- a local legend in Florida’s burgeoning exploitation boom. The rest of the victims are perfunctory, though I did like Yvonne Gilbert’s take on poor Beverly, who corrects Buckman’s grammar even though she is about to be squished. And speaking of Buckman, Jeffrey Allen, whose real name was Taalkeus “Talky” Blank stole the movie. And Lewis found him so endearing, he continued to use the actor in future films.

The film itself took 15-days to shoot, as the production of Two Thousand Maniacs took over the sleepy little retirement community of St. Cloud, Florida, near Orlando. And despite the grisly subject matter, the town apparently embraced the filmmakers, giving them free rein to shoot wherever they wanted, and happily served as extras for all the crowd scenes. They even turned over the town’s fire truck so Lewis could use the ladder and bucket to get a few crane shots for the opening segments when the visitors first arrive in town. And later, the city fathers agreed to chop down several trees in the park for the Teetering Rock sequence because their shadows were ruining the shots. Of course, one year after the production, Walt Disney broke ground on DisneyWorld, which eventually gobbled up St. Cloud as it expanded, meaning the ground of all that death and debauchery is now part of the Magic Kingdom. You can’t make this stuff up, Boils and Ghouls.

Lewis and Friedman would complete the Blood Trilogy with the follow up feature, Color Me Blood Red (1965), but trouble was brewing on many fronts. First, people were starting to copy their formula -- Richard Flink’s even more bonkers Love Goddesses of Blood Island (1964), Ted V. Mikels’ The Undertaker and His Pals (1966); and second, Lewis, Friedman and their executive producer, Sid Reich, filed a lawsuit against their principal financier, Stan Kohlberg, who had promised them with the money they had been making on the Blood Films he could secure them a loan to fund a permanent film company.

Well, turns out this was all a ruse, and Kohlberg had been skimming profits. And as the lawsuits dragged on, Reich died, and Friedman settled out of court on his own and moved to California, leaving Lewis behind holding the bag. This perceived betrayal ended their seven film partnership and their friendship until the two reconciled two decades later. Both men would continue making films on their own, but their individual output suffered greatly from each other’s absence in my opinion.

I don’t know what it is about these primitive gore effects that get under my skin so much. It’s weird, but I find them more revolting and effective than the more polished and streamlined and “more realistic” splatter effects work of more modern films. And don’t get me started on digital blood spatter! Lewis would cycle in and out of the gore game over the next decade or so, rotating between The Gruesome Twosome (1967) and A Taste of Blood (1967) and more violent yokelism and satire with This Stuff'll Kill Ya! (1971) and Year of the Yahoo! (1972) before circling back with The Wizard of Gore (1970) and The Gore Gore Girls (1972). And as the man said, his films were like the poems of Walt Whitman. They’re no damned good, but they’re the first of their kind. Amen, brother, pass the Kaopectate, and chitlins forever, ya’ll!

What is Hubrisween? This is Hubrisween! 26 Days! 26 Films! 26 Reviews! And now, Boils and Ghouls, be sure to follow this linkage as The Fiasco Brothers and Yours Truly countdown from A to Z all October long! That's 24 reviews down with just two -- count 'em, two, more to go! Up Next: Not a Whodunit but an IthinkIdunit.

Two Thousand Maniacs (1964) Jacqueline Kay :: Friedman-Lewis Productions :: Box Office Spectaculars / P: David F. Friedman / D: Herschell Gordon Lewis / W: Herschell Gordon Lewis / C: Herschell Gordon Lewis / E: Robert L. Sinise / M: Larry Wellington / S: Connie Mason, William Kerwin, Jeffrey Allen, Shelby Livingston, Ben Moore, Jerome Eden, Gary Bakeman, Stanley Dyrector, Linda Cochran, Yvonne Gilbert, Michael Korb, Vincent Santo, Andy Wilson

No comments:

Post a Comment