As it is with most holiday traditions, the problem is they just won’t die. And due to some family festivities running a bit long on Christmas Eve, coupled with a harrowing drive home through some hellacious fog, the 10th Annual All-Night Christmas Craptacular Movie Marathon had to be pushed back to Christmas Day, where once again, again, armed up with the usual pecan pie, a giant bottle of Root Beer, and a turkey sub sammich, I settled into the recliner for Operation: A Very Bronson Christmas and Happy Urban Renewal to You and Your Seasonal Affective Disorder Death Wish Armageddon New Year.

Now, despite its Best-Selling source material, I'm sure most folks associate the Death Wish brand with actor Charles Bronson and not author Brian Garfield. Sure, the initial feature film the novel spawned was pretty good, which, in turn, spawned a slew of asinine but highly entertaining sequels; but honestly, even the more serious overtones of the first film kinda sells Garfield's book short.

First published in 1972, the novel itself is only 219-pages long and Paul Benjamin, CPA by day, aspiring vigilante by night, doesn't even get his hands on a gun until page 154. Instead, what we get is a terse and tense psychological study of a good man breaking down emotionally and getting derailed during the grieving process after his wife is killed and his daughter is raped and traumatized for life by a pack of hoodlum home invaders in the demilitarized New York City of the 1970s.

And in an interesting twist, Benjamin never does find out who attacked his family and therefore never achieves any kind of cathartic revenge; instead, he only shoots junkies, petty thieves, and a juvenile gang of vandals for throwing rocks at a subway train.

It's like watching a slow-motion car wreck as Benjamin is first crippled by fear that he slowly overcomes through rationalization, which justifies his course of action of fighting back. There's also a whole chapter dedicated to a published interview by a forensic psychologist who hits every nail on the head on what bred this vigilante. And whether you agree with how Benjamin implements this ever-escalating "therapy sessions" or not, it is completely understandable why he does it. And that is what’s really scary about Garfield’s book.

Originally, the film version of Death Wish was set to be adapted by United Artists and directed by Sidney Lumet, with a long line of actors allegedly up for the role of Paul Benjamin -- changed to Kersey in the finished script. This list included Jack Lemon, Burt Lancaster, George C. Scott, Lee Marvin, Clint Eastwood, Frank Sinatra, Steve McQueen, Gregory Peck and, according to The Hollywood Reporter, Elvis Presley. (Wow.)

According to Garfield, the film was finally set to commence with Jack Lemon in the lead but then Lumet backed out to do Serpico (1973) and Lemon soon followed. And as the producers scrambled for replacements, the option on the book ran out, allowing Michael Winner and Charles Bronson -- with a financial assist from Dino De Laurentiis -- to pounce on the property for Paramount.

The honest to god social commentary of the first Death Wish (1974) film kinda makes me feel bad for lumping it in with the mounting stupidity and misogyny of the sequels. The attack on Kersey’s family is harrowing and brutal and difficult to watch, as it should be (-- though it does show director Winner’s perverted preference for oral sodomy as his favorite form of sexual assault. *bleaurgh*).

Credit to Bronson, too, for his portrayal of Kersey; a conscientious objector who knows his way around a firearm, whose character follows fairly close to the novel as our vigilante evolves. Bronson was honestly trying to play a character here, and not just riding it out on his persona as he would do in later roles.

The film was also a wonderful snapshot of dirty old New York City, and a case study in some truly hideous interior decorating. Mention should also be made of the supporting cast, mostly unknown New York character actors at the time, including Jeff Goldlum as one of the rapists, Vincent Gardenia, Paul Dooley, Christopher Guest, Olympia Dukakis, Stuart Margolin, and Sonia Manzano (-- Maria from Sesame Street), who was Winner’s girlfriend at the time. And it was Manzano who suggested Herbie Hancock to do the film’s offbeat score.

One should also appreciate the fact that Kersey’s victims don't go quietly and the dire effect this initially has on our vigilante. But I think this film might have less to do with vigilante justice and more to do with the inordinate amount of press coverage and police resources spent to catch Kersey for killing criminals as opposed to what was done to catch the criminals in the first place. And the moral gray area faced by the NYPD, who cannot deny the positive effect Kersey’s actions are having on crime rates; and so, they’re less interested in catching the vigilante and more interested in quietly running him out of town.

And this they do, with an open-ending in Chicago that not-so-subtly suggests Kersey’s job is far from finished no matter where he winds up living.

But it would take over eight years before Kersey’s story would continue, thanks to the Go-Go Boys of Cannon Films -- Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, who were looking to legitimize their gonzo product by adding some star power and resurrecting known IP and moribund franchises.

Thus, after obtaining the rights from Big Dino D and signing Bronson to a multi-picture deal, Golan was set to direct Death Wish II (1982); but at Bronson’s insistence, they hired Winner to pick up from where they'd left off. Bronson also had few other demands; one, the film had to be set in Los Angeles so he could remain close to home; and two, with Jill Ireland, his real life wife, cast to play his love interest, the star forbade that anything unseemly should happen to her onscreen.

Not to worry, said Winner, who just brought Kersey’s catatonic daughter back from the first movie and introduced some fodder with a family maid to get attacked and raped in vividly excruciating detail to make our hero take up a gun again. Now, the maid dies in the process, while the daughter commits suicide in a fashion that ends just as tastefully as you’d think.

From there, Kersey goes on a search and destroy mission, targeting only those who killed his daughter and not just some random schmucks on the street -- though it’s kinda comical how he never seems to run out of bullets. There’s also an asinine subplot involving a returning detective from the first film (Gardenia), who aimlessly follows Kersey around, commits a few out-of-jurisdiction felonies, and then dies in a shoot-out saving our hero’s hash.

And then things really go off the rails when the cops get to his last target first, who is then safely ensconced inside a mental hospital, forcing Kersey to take some drastic measures and sacrifice the love of his life to complete this bloody vendetta.

Yeah … Remember all that social commentary I was touting in the first one? Well, forget it. Okay, maybe there is a little social commentary in Death Wish II; it's just been put through the Go-Go Boys filter and then shot out of their Cannon, leaving the audience to sift through the unseemly debris to find it.

If you’ve watched the excellent documentary Electric Boogaloo: The Untold Story of Cannon Films (2014), you'll remember no one had anything nice to say about the megalomaniacal Winner, painting him as a sadistic pervert. And from what we've seen onscreen, well, the criticism seems pretty damned valid. Still, this rehash was a big hit for Cannon and Filmways, who distributed it, meaning another sequel was soon in the works.

However, between the release of Death Wish II and the production of Death Wish 3 (1985), it probably should be noted that two things happened. One, Golan felt general audiences were too stupid to understand Roman numerals; and two, life imitated art as native New Yorker Bernhard Goetz shot and seriously injured a gang of four men who were allegedly trying to mug him. Brought up on attempted murder charges, the real-life "Subway Vigilante" was acquitted of everything except for the charge of carrying an unlicensed gun. (He would later lose a massive civil suit.)

Now, I for one have never believed in Woody Allen's New York, but felt Michael Winner, Frank Henenlotter, Abel Ferrara, Sydney Lumet and the TV show Barney Miller (1975-1982) were a little closer to the truth about life in the Big Seedy Apple back in the 1970s and '80s. Regardless, Goetz was both vilified and championed for his actions, just like his big screen counterpart.

Meantime, Michael Winner loved the idea of Paul Kersey as the hero of the people, facing down a street gang that had been terrorizing elderly citizens and commissioned a screenplay from Don Jakoby, who wrote the scripts for Tobe Hooper's Lifeforce (1985) and Invaders from Mars (1986) -- two more high profile flops for Cannon Films, essentially turning Kersey into an urban John Rambo.

True to form, despite a ton of flack over the utter crassness of the first sequel, Winner took Jakoby's script and pulled out all the stops, kept in all the exploitative and salacious elements from the second film, and then added a metric ton of stupidity, escalating things from covert vigilantism to open warfare on the streets -- to the mortification of Jakoby, who had his name removed from the credits, and his star, Bronson, who found the resulting escalation of violence pure nonsense.

Here, Kersey returns to New York when an old friend who knows what he's capable of sends him a desperate plea for help. Seems his tenement and neighborhood are under siege by a local crime element, led by Poor Man's Jake Busey, Gavan O'Herlihy. Alas, this message came too late as this friend gets murdered by some colorful post-apocalyptic street punks who, I assume, were leftover extras from Golan's The Apple (1980).

Then, in another twist, this time, Kersey has the full backing of the local police precinct because, and I quote, “He can do what they can't.” And what he can do is murder the living hell out of people with extreme prejudice. Eventually.

Yeah, its not until after Counselor Troi from Next Gen gets gang-raped, his new bestest bud (Martin Balsam) gets chucked out of a second story window, and Kersey's newest expendable girlfriend (Deborah Raffin) takes a one-way trip down a very steep hill in a very combustible Buick (-- because Martin Balsams bounce and Combustible Debora Raffins combust, that's why --) before our hero finally makes his stand.Murder! Murder! Murder!

Now fully on the warpath, Kersey starts out small, using a board with a nail in it; and then a bigger board with a bigger nail it; but then gets serious with a 30-caliber machine gun and a bazooka in his one-man crusade for urban renewal, making the final score: Body Count - 83, Due Process - 0.

I guess if watching bad movies teaches us anything, we know we shouldn't meddle with a Native American burial ground, get on a plane if William Shatner's on board, and to never, ever, become romantically involved with Charles Bronson in a Death Wish movie or your sentence is a forgone and ludicrous death.

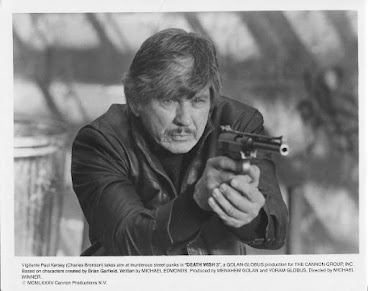

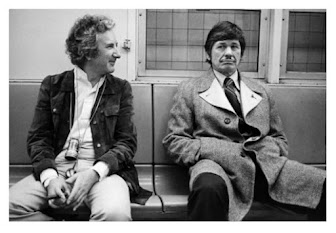

Michael Winner and Charles Bronson, Death Wish (1974).

You know, there are days where I really wish I could live in the Menahem and Yoram (Mayhem and Urine to others) Cannon universe where crap like this, The Apple, Ninja III: The Domination (1984) and Breakin' (1984) can happen. Actually, it would be kinda cool if all of those were in the same shared universe. Noodle that one for a bit, true believers. Also, Death Wish 3 is everything Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan (1989) could've and should’ve been, dammit.

Okay. Apparently, Winner and Bronson had a massive falling out during the filming of Death Wish 3 over *ahem* “creative differences,” which meant the controversial director was out and J. Lee Thompson was in for Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (1987).

As originally scripted, the film would borrow heavily from the plot of another Thompson, Bronson and Cannon collaboration, 10 to Midnight (1983), with Bronson's matrimonial ambitions once more ending in the rape and murder of yet ANOTHER spouse! But this time he catches the creeps and turns these perpetrators over to the police -- only they wind up getting released on a technicality, pushing Kersey back into murder-bot mode.

But these notions were scrapped for something different. Well, sort of different. But not really. See, this time, when the daughter of his latest flame (Kay Lenz) dies of a drug overdose, Paul Kersey declares war on cocaine; and when Kersey declares war on drugs, just “Saying No” ain't gonna cut it and, between you and me, cocaine totally had it comin’ and doesn't stand a chance.

From there, Kersey is kinda clumsily plugged into a botchilized dinner theater production of Yojimbo (1961), where, under the guidance of a tabloid publisher (John P. Ryan), who also lost a daughter to drugs, our vigilante is essentially hired to ‘piss in the pot’ of two rival trafficking factions, setting them against one another with some strategic hits, and then lets them wipe each other out. This works remarkably well until a late monkey-wrench in the plan surfaces and Kersey finds out he's been duped into clearing out the competition for a new player.

Honestly, Death Wish 4 isn't half bad as far as mid-80s action vehicles go. In fact, the climactic shoot-out at the roller-disco and video arcade is really quite good with some outstanding set-ups by Thompson and DP Gideon Porath. Once more, the main bad guy meets a rather hilarious exploding end at the hand of a rocket-propelled grenade.

And, oh, Holy Crap! Poor Kay Lenz. She basically disappears for half of the movie, tucked away somewhere safe, only to wind-up a hostage for the grand finale. And then, to the shock of nearly everyone, our expendable love interest appears set to survive -- only to finally be gunned down with only four, FOUR, four goddamned minutes to go in the film. Sorry, lady, I was really pulling for ya there. And while definitely a record for longevity in one of these things, she still never had a chance in this franchise, making this afterthought killing even more sad and cruel.

Now, by the time the fourth Death Wish sequel went into production, after a string of high profile flops and over-extension on all fronts, Cannon Films was in some deep financial doo-doo. A lot of corners were cut during the production of Death Wish 4, most notably the soundtrack, where it was completely scored with tracks from earlier films, including Missing in Action (1984) and Invasion U.S.A. (1985).

And after Cannon finally collapsed and the Go-Go Boys split-up, Menahem Golan, while trying to make a comeback, independently financed another sequel, Death Wish V: The Face of Death. And while I had every intention of watching it as well, alas, Amazon did not have this installment streaming like the first four, meaning our 10th Annual All-Night Christmas Craptacular Movie Marathon came to a premature end. Boo! I said, Boo!

Well, I wouldn't say the evening was ruined, as memory serves the fifth rehash was the EXACT same movie as part 4. Not as nutty as part 3, or as vile as part II, and his new girlfriend dies a lot sooner, and her transvestite killer gets offed by an exploding soccer ball. And so, there ya go.

"There's no moralistic side to Death Wish,” said Michael Winner. “It's just a pleasant romp." Said Brian Garfield, who was mortified by the entire film series based on his book, "They'd made a hero out of him. I thought I'd shown that he'd become a very sick man.” When asked, I’m sure Bronson squinted a little harder before grunting something.

As for me? Well, I think the first film has merit, and find the second heinously vile on almost every level; the third is relatively harmless and a hare-brained train-wreck of awful that borders on self-parody; and then the fourth is actually a pretty good movie of the era and vintage.

Put them all together and you got a tonally inconsistent mess that will probably resemble my stool sample in the morning after consuming all that pie and turkey. And with that, I wish you all a Merry Christmas and Happy Holiday, Boils and Ghouls. Or Bah! Humbug, where applicable.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)