We open with a brazen and well-orchestrated early morning bank robbery, which progresses smoothly until a guard goes for one of the perpetrator’s guns but winds up shot and killed as the two assailants flee with almost $200,000. Cut to several days later, where we zero in on a young woman, Lona McClane (Novak), as she vacates a movie theater and heads for her car. Only her car won’t start. Luckily, a good Samaritan just happened to be passing by, who offers some assistance.

Thus, Paul Sheridan (MacMurray) helps the stranded motorist get the vehicle to a mechanic and gives her a ride home. But they stop at a bar for a drink along the way, and then divert to his apartment, leaving it up to the audience as to what happens next when the door closes. But if we were all betting folk, odds are good these two just had sex. So, place your bets now.

The next morning, Sheridan heads to work and, turns out, he’s a police officer. And not only that, but this detective has been assigned to crack that bank robbery case. Also of note; turns out Lona is/was the girlfriend of Harry Wheeler (Richards), one of those robbers identified by several eyewitnesses. (The other, who shot the guard, wore a mask.) And so and so, Sheridan was actually tailing Lona, hoping she would lead him to Wheeler, the money, and the identity of his partner. So, yeah, you’d be right to assume that *ahem* “assignation” at his apartment, which explains why he didn’t want to return to hers, which is under constant surveillance, really wasn’t proper police protocol for such a stakeout.

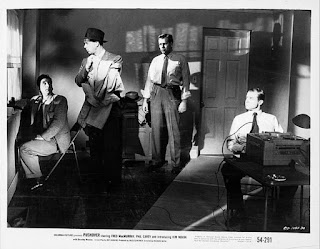

You see, Sheridan, along with his partner, Rick McAllister (Carey), have been clandestinely watching Lona’s apartment and listening in on her phone calls for quite some time now from an adjacent building. (And when she leaves, one of them has to follow ‘natch. And three guesses as to who ALWAYS volunteers for THAT detail.) They’ve also been saddled with another detective on their shift, Paddy Dolan (Nourse), whose penchant for abusing the bottle is about [-this-] close to blowing his impending retirement pension.

And so, under direct orders from their hard-nosed Lieutenant, Karl Eckstrom (Marshall), Sheridan and McAllister must not only keep a close tab on Lona they must also effort to keep Dolan sober for just one more week, and they do this by leaving him alone in the car. To watch the street. Parked right next to a bar. Once again, place your bets, folks.

Anyhoo, as this stakeout dragged on, Sheridan soon became infatuated with the drop-dead gorgeous femme fatale -- so much so, they decide to meet up at his place again. Only this time, Sheridan blows his cover by asking too many questions about Wheeler. Despite this betrayal, Lona seems to have genuinely fallen for this old rugged cop and sets her hooks in deep. And so, soon enough, Sheridan’s unhealthy desires soon have him scheming to kill Wheeler and keep Lona and the money all for himself...

Poor Fred MacMurray. He never could fall for the right dame in these old noir films. And I guess one could (fairly easily) draw comparisons between Pushover (1954) and the noir film to end all noir films, Double Indemnity (1944) -- especially the sense that the whole scheme and machinations in both MacMurray-led films -- one a double cross on a bank job, the other a homicidal case of insurance fraud -- felt doomed from the start, making these roads to ruin a distinct inevitability.

Like Double Indemnity, which was based on James M. Cain’s novel, Pushover also began life as a book, The Night Watch, by Thomas Walsh, which also was serialized as The Killer Wore a Badge in The Saturday Evening Post from November through December in 1951. To adapt Cain’s novel into a screenplay, director Billy Wilder looked to Raymond Chandler, one of thee greatest writers of detective fiction of ever (The Big Sleep, Farewell My Lovely, The Long Goodbye). And to adapt Walsh’s novel, director Richard Quine looked to Roy Huggins, who was soon to become equally famous in the world of detective stories -- only in a different medium.

A novelist himself, Huggins career in Hollywood began when Columbia Pictures optioned the rights to his novel, The Double Take, and turned it into I Love Trouble (1948). But before he would sign the contract, Huggins stipulated he be allowed to adapt his own work. After, Huggins stuck with Columbia for a few years, bouncing between them and RKO, writing scripts, adapting more of his own literary output with the terse melodrama Too Late for Tears (1949) -- where another money grab goes horribly wrong, and riding out the Communist witch-hunts of that era. Seems Huggins had actually joined the Communist Party back in 1939 but would renounce them less than a year later when the Soviets became allies with Nazi Germany. Huggins was called to testify before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee, where he proved cooperative, naming 19 other party members but only named names of those who had already been outed.

And so, Huggins avoided the dreaded Hollywood Blacklist and continued producing screenplays, most notably a trio of westerns -- Gun Fury (1953), Three Hours to Kill (1954) and the Randolph Scott vehicle, Hangman’s Knot (1952), which also saw Huggins take a rare shot at directing. But by 1955, Huggins shifted gears and mediums, moving to the small screen, taking jobs with Warner Bros. and 20th Century Fox’s TV divisions, where he produced hits like Cheyenne (1955-1963) and Maverick (1957-1962) -- an offbeat western starring James Garner (-- followed by Jack Kelly and Roger Moore), where Huggins guiding principle for his pool of writers went as follows: “In the traditional Western, the situation was always serious but never hopeless. In a Maverick story, the situation is always hopeless but never serious.” Around the same time Huggins also helmed the smash hit detective series 77 Sunset Strip (1958-1964).

Unhappy with how Warners treated him financially during this period, feeling they were constantly cheating him out of owed royalties, Huggins quit and joined Quinn Martin Productions, where he produced his biggest hit yet, The Fugitive (1963-1967), which Huggins always vehemently insisted was not based on the notorious Dr. Samuel Sheppard murder case but was, instead, intended to be a modern-day take on Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable, with David Janssen’s Dr. Richard Kimble as Valjean and Barry Morse’s Lt. Gerard subbing in for Javert, who chases Kimble while he chases down the one-armed man. But by the mid-1960s, Huggins had moved on to Universal, becoming vice-president of the TV division, where he would serve for nearly two decades, launching shows like The Virginian (1962-1971) and The Bold Ones (1969-1972).

And when the 1970s rolled around, after the Butch and Sundance cash-in Alias Smith and Jones (1971), Huggins left the western behind and started telling offbeat detective stories again, with things like Toma (1973) and Barreta (1975-1978), but then reached the absolute zenith of the small screen take on the genre when he teamed up with Stephen J. Cannell for The Rockford Files (1974-1980), once again featuring Garner as a pardoned ex-con turned acerbic and often reluctant detective who knew every scam in the book and could never get into his trailer without getting jumped by a few thugs -- especially if he had just been to the grocery store. Few shows were better. And Cannell, a TV legend himself, who also worked with Huggins again in the 1980s on Hunter (1984-1991), said of the veteran writer/producer, "Roy was in the driver's seat where he belonged. Nobody does it better or with more style...Roy Huggins is my Godfather, my Hero and my Friend. They don't come any better."

Huggins was still producing TV movies based on his properties up until his death in 2002, ending a remarkable career and a ton of hits that ran for nearly four decades. And while his work in film wasn’t quite as indelible, you can still see that Huggins’ “touch” in his screenplays, where ordinary, everyday but very fallible people soon find themselves in something completely over their heads.

Pushover would be one of the last screenplays Huggins would write, and one of its greatest joys is watching the wheels come off as Sheridan’s solid and near foolproof plan to rub out Wheeler, steal the girl and the loot unravels and goes completely awry while his desperate attempts to salvage it only makes things exponentially worse.

In the beginning, it appears this plan will go off without a hitch. And things are helped out considerably due to Sheridan’s partner becoming equally fascinated with Lona’s next door neighbor, a nurse named Ann Stewart (Malone), who is constantly distracted by her as they keep bumping into each other as McCallister lurks about. But this comes back to bite Sheridan in the ass when Ann, looking to borrow some ice for a party, finds Sheridan in Lona’s apartment when he isn’t supposed to be, making her a dangling loose end that will most likely have to be dealt with, and permanently.

And then there’s Paddy, who isn’t where Sheridan needs him to be for this plan to work but is instead inside that bar knocking a few back -- only to reappear at the most inopportune time. And so, Paddy kind of screws the pooch when Wheeler does show up. And when Sheridan’s attempt to soft-strong arm Paddy into accepting why his fellow cop had to kill Wheeler in a clumsy audible, Paddy, a drunk but no fool, doesn’t buy this cock 'n' bull is all about saving his pension at all. And that’s why Paddy moves the car with the money and the body in it on his own. And so that’s also why Sheridan accidentally kills him later when Paddy refuses to say where it is and threatens to turn him in.

And as the cops swarm in due to the gunshot, Sheridan tries to play this off as a suicide. And this buys him some time -- but not quite enough, as McCallister backs his story, having seen Paddy in the bar drinking. But his story starts to fall apart as the lies and spin mount, and Lt. Eckstrum is starting to smell a rat. And as the evidence starts pointing back toward him, Sheridan is soon on the run with Lona, who found Wheeler’s car and the loot in the interim.

And they might’ve still gotten away clean if Sheridan hadn’t detoured to take care of Ann, kidnapping her, leading to pretty cool game of cat and mouse as they try to get their disposable hostage out of the building and through the surrounding police dragnet -- stress on the might’ve.

Now. One of the other great pleasures of watching Pushover is getting to watch both the lovely Kim Novak and the gorgeous Dorothy Malone as the bad girl / good girl foils do their respective thing. I’m still not convinced that wasn’t Novak as the model used to lure Gaucho into making a movie for Jonathan Shields in The Bad and the Beautiful (1953). Either way, Lona McLane would be her first credited screen role. She would officially break out two years later in Picnic (1955), and would go on to torment Jimmy Stewart (and Alfred Hitchcock) in Vertigo (1958).

I think I first encountered Malone in Beach Party (1963), where I officially fell in love. She won an Oscar in 1956 for Written on the Wind but I still contend her best performance was in The Last Voyage (1961), one of the best disaster movies you’ve probably never heard of. Again, I cannot express how much these two drop-dead knockouts in those period fashions are worth the price of a rental alone.

Stitching all of this intrigue and eye-candy together was Richard Quine, one of Sam Katzman’s merry brigade of schlockmeisters making hay in Columbia’s B-units. The film was shot in downtown Burbank near the old Magnolia Theater -- featured prominently in the film. Shot mostly at night, with lots of rain and neon reflecting off the puddles, Quine manages to bring the usual noir trappings into this mounting melodrama, and manages to maintain the tension throughout Pushover as the noose finally closes around our hero’s neck and his journey down this ruinous road comes to its fatal end. A familiar journey, sure, but still well worth the time traveled inevitable or not that ending may be.

Pushover (1954) Columbia Pictures Corporation / P: Jules Schermer / AP: Philip A. Waxman / D: Richard Quine / W: Roy Huggins, Thomas Walsh (novel) / C: Lester White / E: Jerome Thoms / M: Arthur Morton / S: Fred MacMurray, Kim Novak, Philip Carey, Dorothy Malone, E.G. Marshall, Allen Nourse, Paul Richards