Almost six months have passed since World War II ended in September, 1945, and the bucolic town of Texarkana, which straddles the border between Texas and Arkansas, effectively making it two cities, had been slowly adjusting to this post-war climate. Mustered out servicemen were returning home by the hundreds to begin the long and tedious process of readjusting to civilian life. Anxiety that a government munitions works, one of the largest employers in the area, would shut down with the cessation of the war proved unfounded as the depot would remain open. And so, it appeared Texarkana, a town of good, friendly, and hardworking people, was about to experience a period of optimism and prosperity -- until a cold night in March, as the full moon shined above, turned deadly, which was only the beginning of four months of terror and paranoia that would temporarily derail this postwar boom.

It all started when Sammy Fuller and Linda Mae Jenkins (Hackworth, Fullworth) find a secluded spot on some back-road after catching a movie in town to do what most young couples do on these makeshift lover’s lanes in the dark. But Linda Mae isn’t really feeling it, distracted by an unease someone is watching them, much to Sammy’s consternation. And while he appears ready to give up and call it a night after getting stuck at first base, both are startled when the car hood suddenly pops open, and then just as quickly slams shut, revealing a hulking figure with a white canvas sack pulled over his head leering back at them through two slits cut into the cloth. And as this masked man angrily shakes the distributor cap he’d just torn off the engine at the them, making it impossible to start the car, Sammy tries it anyway but no soap. Meantime, the assailant breaks out the driver’s side window with a pistol and pulls the driver out, slicing him up badly on the broken glass. And once the boyfriend is subdued and out of the way after a savage pummeling, the attacker enters the car and slides across the seat toward the screaming Linda Mae.

Cut to the next morning, where a passing motorist finds Linda Mae by the side of the road -- alive, but barely. Once the County Sheriff is alerted, his chief deputy, Norman Ramsey (Prine), finds the original crime scene at the car and discovers Fuller has also miraculously survived despite being shot multiple times. Later, at the hospital, Ramsey is joined by Sheriff Barker (Aquino) for a debriefing by the medical staff who treated the victims, which reveals both were shot and severely beaten; and while the girl was not raped her back, stomach, and breasts were heavily bitten; literally gnawed on. Unsure of what they’re dealing with, an uneasy Ramsey pays a visits on R.J. Sullivan (Citty), the Chief of the Texas-side Texarkana P.D., thinking they might want to warn the local teens of what happened, to be alert, and maybe arrange some joint patrols of the isolated roads around town just in case this attack wasn’t a fluke. Strapped for money and manpower, just like the Sheriff’s department, Sullivan offers to do what he can.

Three weeks later, despite nary a sign of this newfangled boogeyman, Ramsey still patrols the country lanes and back-roads around Texarkana until he comes upon a parked car on the side of the road. He gets out into the pouring rain for a closer look but the car is empty. Suddenly, he hears gunshots nearby. And after calling in his location and a request for backup, he heads to where those shots came from, where he finds Howard Turner, dead in a ditch, his face beaten to a pulp with two bullet holes in the back of his skull. Further up the road, he finds Turner’s girlfriend, Emma Lou Cook, also dead of multiple bullet wounds to the head, tied to a tree, covered in human bite-marks. Ramsey also spots the hooded killer fleeing the scene in a car but the rain is too heavy and the car too far away to get the plate number or get a shot off with his scatter-gun.

When ballistic tests definitively link these two heinous crimes, panic grips the area, resulting in a run on local gun stores and pawn shops and a boom in home security sales as locks are reinforced and windows are boarded up against the looming threat of what the press have dubbed the Phantom. Having never dealt with this kind of deadly and unmotivated menace before, Barker and Sullivan arrange to bring in some outside help in the form of legendary Texas Ranger, Captain J.D. “Lone Wolf” Morales (Johnson), to takeover and jumpstart their stalled investigation. Ramsey is assigned to assist Morales, as is city patrolman, A.C. “Sparkplug” Benson (Pierce). As Ramsey gets the Ranger up to speed, and Sparkplug makes a total ass of himself, the deputy explains his theory; how he believes the killer will strike every 21 days to coincide with the cycle of the moon, meaning he is destined to attack again when the city high school holds its prom. Morales finds this assessment sound. And so, on the fateful night, several decoy cars and couples made up of city, county, and State cops, half of them in drag, are staked out at secluded spots outside of town, hoping they will draw the Phantom out.

Meantime, back in town, the prom is just wrapping up with the last dance. And as everyone heads home, the band starts breaking down and packing up, including trombone player, Peggy Loomis (Butler), who, with instrument in tow, meets up with her boyfriend, Roy Allen (Lyons). And despite all the warnings, Roy isn’t ready to go home just yet and wants some *ahem* ‘alone time’ with his girl. Peggy is reluctant, and rightfully so, but he offers they can just drive to Spring Lake Park, which is located in the middle of town, where he assures they will be safe. Still worried, Peggy agrees to this compromise. Alas, these two unsuspecting teens are about to find out the hard way that nowhere is safe from the Phantom killer, and will pay for this mistake with their lives -- and pay most gruesomely...

The anomalous twin city of Texarkana came into being in 1873 when two rival railroad lines -- the Cairo-Fulton Railroad, which was headed west, and the Texas-Pacific, which was headed east, negotiated a junctioning just south of the Red River on the Texas-Arkansas border and started selling off parcels of land to settlers, who would eventually form the town when it was incorporated on the Texas side in 1874 and on the Arkansas side in 1880; and both sides have been feuding ever since over who controlled what. Even it’s naming was in error, when a surveyor thought it was located where Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana met, resulting in Tex(as)-Ark(ansas)-(Louisi)Ana.

And so, from its inception, through the Civil War, through the turn of the century, through Prohibition, and through the Depression, Texarkana has endured a contentious and volatile history and developed a notorious reputation as a haven for bootleggers, illegal gambling, prostitution, political corruption, and crime both organized and not so organized. There were even rumors the notorious State Line Mob’s influence reached into the city limits, earning Texarkana the nickname of Little Chicago, joining places like Phenix City, Alabama, Omaha, Nebraska, and Calumet City, Illinois, as the most corrupt places in the country when World War II came to an end.

And so, dealing with a jurisdictional no-man’s land that spanned two States, two counties, two (half) cities, and the resulting bureaucratic chaos, little was done to effectively stop or even curb this illegal activity as any organized resistance was next to impossible due to a lack of coordination or cooperation between six different law enforcement agencies, who were often on the take, and who, like everyone else, didn’t really get along. And so, with that backdrop in place, if you wanted to get away with murder, Texarkana sure seemed to be the place to try it. And try this someone did. Remember, in 1946 the term serial killer hadn’t been invented yet, and it would be well over a decade before Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate introduced the term thrill-killer to the masses. And for a period of four months in early ‘46 the city of Texarkana and it’s surrounding counties were hit by a brazen and brutal combination of both in a string of deadly assaults perpetrated by a person or persons unknown.

The first attack occurred in February that year, when Jimmy Hollis (25) and Mary Jeanne Larey (19) were parked on a lonely road outside the city in rural Bowie County, Texas, where they were accosted by a large man, his features hidden beneath a burlap sack, who forced them out of the car at gunpoint, then pistol-whipped the boy, fracturing his skull, before chasing down and sexually assaulting the girl, who had tried to escape. The masked man then fled when another car approached the area. Both victims survived the attack. The next two weren’t so lucky as the assailant struck again one month later in late March, when Richard Griffin (29) and Polly Anne Moore (17) were found shot dead in the back of Griffin’s parked car. Blood evidence at the scene that wasn’t trampled by looky-loos showed the couple was most likely killed outside the car and then moved; and a postmortem showed Moore had been sexually assaulted.

And yet it wasn’t until after a third attack and two more deaths before the very notion these cases were connected and possibly committed by the same man ever occurred to anyone. This latest double-homicide took place on April 14, when the bodies of Paul Martin (16) and Betty Jo Booker (15) were found about a mile apart in Spring Lake Park inside the Texas-side city limits. Like the other couples, Martin had been beaten and shot twice. And Booker, also fatally shot, would show signs of assault and of being redressed postmortem. And when forensic tests showed all four victims were killed by a .32, this is what finally got the quarter to drop for the local authorities and the FBI that there was a madman loose in Texarkana who would most probably kill again.

And once this theory leaked to the local press, they quickly latched onto it and had a sensationalist field day, printing rumors as fact and theories as gospel. Headlines screamed "Sex Maniac Hunted in Murders" and "Phantom Killer Eludes Officers as Investigation of Slayings Pressed" and "Phantom Slayer Still at Large as Probe Continues". It was the managing editor of the Texarkana Gazette, Calvin Sutton, who officially tagged the killer as the Phantom, taking inspiration, perhaps, from the admats for a local theater that was currently showing a murder mystery, The Phantom Speaks (1945).

And it was all of this cumulative yellow ink after the third attack that pushed the already panicked citizenry of Texarkana into a paranoia-induced mass-psychosis as people armed themselves against the threat of the Phantom and deployed booby-traps to sound an alert if the killer was stalking nearby.

And when news of the Phantom went national, thanks to a photo-spread in LIFE Magazine on the Art of Texarkana Home Self-Defense, this triggered another feedback loop of fear-mongering, which led to more false sightings, false leads, and false confessions, and a town that literally feared sundown. And it should be noted it wasn’t until after the second double-homicide and the case became national news before The Texas Rangers got involved, including the infamous M. T. "Lone Wolf" Gonzaullas, who was also a notorious publicity hound. And as Gonzaullas took over the case, he organized setting up surveillance of the back roads that fit the killer’s M.O. and deployed decoys in parked cars, hoping to draw the Phantom out, but the killer never took the bait.

And then, two weeks after the Martin-Booker murders, the Phantom allegedly struck for the fourth and last time, when he broke his pattern and targeted a farmhouse on the Arkansas side, killing Virgil Stokes (37); shot twice in the head through a window while sitting in his living room. His wife, Katie Stokes (36), had been in bed, heard the glass breaking, and found her husband dead in his chair. She moved to call the police only to be shot twice in the face through the same window. And as the Phantom tried to break into the house, the badly injured wife managed to escape and elude the killer, reaching the safety of a neighbor. But by the time the alerted police arrived, the Phantom was long gone. Mrs. Stokes would survive the ordeal, but she never even saw the man who shot her, leaving Gonzaullas with two more victims and no new leads to the Phantom’s identity.

And so, “Murder Rocks City Again: Farmer Slain, Wife Wounded” screamed the headlines the following day. And as the subsequent days passed with no new leads and no suspects, the Texarkana Gazette kept fanning the flames, warning their subscribers “The killer might strike again at any moment, at any place, and at any one,” which sent another massive jolt of Phantom anxiety throughout Texarkana and the surrounding communities, including the little town of Hampton, Arkansas, where a young eight-year-old named Charles B. Pierce spent many a sleepless night worrying the Phantom might be coming for him.

As he grew up, when he wasn’t worried about phantom killers or swamp monsters -- which we’ll be addressing in a second, Pierce was making 8mm home movies with his best friend and neighbor, Harry Thomason. Fascinated by the medium of moving images, Pierce decided to make this his profession. He landed his first job as an art director for KTAL-TV in Shreveport, Louisiana, in the mid 1960s, where he was later promoted to weatherman and played the host for a children’s cartoon show. And after bouncing around TV stations in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, Pierce finally settled in Texarkana, bought himself a 16mm camera, and opened an advertising agency, where he made shorts and commercials for local businesses and eateries.

One of Pierce’s biggest clients was Ledwell and Son Enterprises, who manufactured semi-trucks and trailers, developing a very successful ad campaign for them that ran all over the south. And based on this success, Pierce approached Ledwell about financing a proposed feature film. At the time, Pierce’s old childhood buddy, Thomason, had just written, directed, and shot his own feature; the paranormal thriller, Encounter With the Unknown (1972), which was filmed in and around Little Rock, Arkansas, which made a tidy profit on the initial regional roll-out. Inspired by his friend’s success, Pierce felt he could also shoot a movie locally and make some money. And while Ledwell wasn’t completely sold, he did agree to bankroll the production to the tune of $100,000. And what Pierce had in mind was an ersatz nature documentary, “based in fact,” on a local legend; a Bigfoot like creature that roamed the swamps around Fouke, Arkansas, to cash-in on a rash of recent sightings of the Fouke Monster, dating back to 1971, when the unidentified cryptid allegedly attacked and terrorized the home of Bobby and Elizabeth Ford.

I go more into the history and production behind The Legend of Boggy Creek (1973) in a long and long ago written review for those interested in such things, but for now, what’s important is how Pierce really tapped into something with this faux doc, using a scholarly narrator to give it some weight, employing flashbacks and local raconteurs to tell his story, achieving a folksy verisimilitude -- all on top of some beautiful cinematography, which captures the whole hick mise en scene and lets audiences feel the heat and humidity, smell the peat moss, be mesmerized by the chorus of cicadas, and feel all those psychosomatic skeeter bites, making the mundane feel menacing and pushing the whole enterprise into something that felt like it should’ve been shown on PBS and not at the Drive-In. Well, at least until the third act when things go a little bit … bonkers.

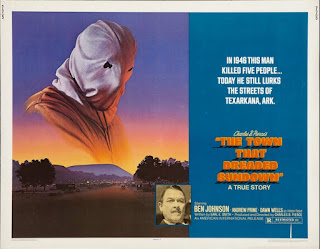

Regardless, Pierce had a huge hit on his hands and made a ton of money by selling The Legend of Boggy Creek to Howco and the TV and foreign release rights to American International Pictures. Taking those profits, Texarkana’s new mini-movie mogul continued making regional pictures, including Bootleggers (1974) and a couple of westerns, Winterhawk (1975) and The Winds of Autumn (1976). And while all were solid enough, none reached the audience fever pitch or financial payoff of The Legend of Boggy Creek. And so, Pierce decided his next project would tap into the same faux documentary style as Boggy Creek. He also decided to base it on another “true story” about another local legend, which was now referred to in hindsight as The Texarkana Moonlight Murders.

Those who worked with Pierce over the years always complimented his enthusiasm but admitted the writer, producer, and director really didn’t know what he was doing but knew exactly what he wanted. And as he exploited and captured the Phantom’s reign of terror, his film, The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976), played pretty close to history and yet played pretty loose with the facts, changing the names of the players and victims to protect the innocent -- and perhaps save himself from a few lawsuits, while taking many dramatic liberties. And none were more egregious or outlandish than his interpretation of the Martin-Booker murders, when their surrogates, Roy Allen and Peggy Loomis, are attacked in State Line Park by the deranged killer.

Following his usual pattern, the Phantom subdues the male first. Here, by jumping on the moving car’s running board and pulling the boy out of the car, causing it to crash into a tree. And as Roy is beaten senseless, a concussed Peggy tries to flee, only to be caught and tied face first against a tree. Once she’s secured, the killer finishes off Roy with his pistol. He then pokes around the car and finds Peggy’s trombone, attaches a knife to the end of the slide, and then uses this to stab the girl in the back, repeatedly, as he “plays” the instrument until she is dead in a truly odd and rightfully notorious scene that should not work, at all, and yet. Comical, and yet. Horrific, but. Most of the credit -- no, all the credit, for making this scene work goes to the actors, especially Cindy Butler as the victim, who really sells the hell out of her own dubious demise.

Once again, the cinematic investigation goes nowhere as leads dry up and suspects are cleared. Baffled by the killer’s irrational methods, Morales and Ramsey confer with a criminal psychiatrist, Dr. Kress (Smith), at a restaurant. Seeking some insight on what makes this killer tick, Kress explains the Phantom is a highly intelligent sadist with a strong sex drive -- but not in the way they think. He’s more interested in inflicting pain than sexual gratification. It is this pain that gratifies him. And as Kress expresses doubts they will ever catch the wily Phantom, we pan down low to another table and see the familiar shoes of the killer, meaning he was privy to the entire conversation, explaining why he was always not one or two but several steps ahead of the law.

Several weeks later, Helen Reed (Wells) is spotted by the person wearing those same shoes as she leaves a grocery store. Later that night, Helen hears something outside and alerts her husband, who heard nothing and returns to his paper. Then, the Phantom appears right behind him in the window, who shoots the unwitting victim in the back of the head. Hearing this, Helen investigates, sees her husband slumped over, dead, and the Phantom, and retreats to the phone in the kitchen.

But before she can crank up an operator, the Phantom crashes through the screen door and shoots her twice in the face. Like her real-life counterpart, Helen manages a daring escape while the killer makes sure the husband was dead and flees into a cornfield, where the Phantom, armed with a pick-axe hunts for her. And after a few harrowing moments, despite her injuries, she manages to reach a neighbor’s house and escapes. Helen survives, but can offer little except a general description.

News of this attack spreads quickly and pushes a city on the brink over the edge. Meantime, Ramsey overhears a report about a stolen car that matches the one he saw fleeing the scene of the first double-homicide. He alerts Morales, and they investigate the sandpit where the car was spotted. Armed with shotguns, they find the car -- and the masked Phantom. Chasing him into the woods, taking several shots at the killer as they go, they reach some train tracks, where the killer manages to get across before a slow moving train cuts the others off. Morales and Ramsey keep on firing and hit him in the leg, but by the time the train clears off the Phantom is long gone.

Like the case of the Moonlight Murders itself, Pierce nor his screenwriter, Earl E. Smith -- who basically wrote all of Pierce’s films, had no real resolution for the film. And over the years since the last attack it was getting mighty hard to separate fact from fiction, which had been occluded by rumors, fallacies, pet theories, and even Pierce’s film. And as the police revisited and true crime experts dug into this cold case, what they found was an investigation plagued by jurisdictional disputes, conflicting witness statements from those who survived, and sloppy crime-scene preservation, leading to who knows how many missed clues.

Also not helping was the out of control local press; for no matter what the newspaper archives said, official police reports were conflicted on whether any of the female victims were actually sexually assaulted or not -- or even if there were autopsies performed on several of the victims at all. Other sources said all the women were molested and penetrated by a foreign object; most likely the pistol. What we do know for sure is none of the victims were gnawed on as the film contends. Was this something Pierce felt he could get away with instead of showing what really happened, which he probably couldn’t get past the censors? Or as the old axiom goes, When the bullshit is more titillating than the truth, film the bullshit.

And to modern forensic eyes, some experts aren’t even sure if the first assault and the last attack were even connected to the other two. Yet others contend the Phantom was responsible for even more victims, including a woman, Virginia Carpenter, who knew three of the Phantom’s victims, who disappeared without a trace almost two years later in 1948, and a man named Earl McSpadden, who was found in pieces near a railroad tracks not long after the attack on the Stark's house; but the D.A. and coroner couldn’t agree if the man had been stabbed first before being dismembered by a passing train or not.

Some even think McSpadden was the Phantom, since the killings stopped after he died accident or not. (And this whole incident provided one of the main plot-points in the ill-conceived 2014 reboot-remake-whatever-you-wanna-call-it of The Town that Dreaded Sundown). There were plenty of other solid suspects over the years, too, including a college student who left a written confession to the killings before committing suicide, who was later exonerated by a postmortem alibi. There was talk of it being an escaped German POW, and a former tail-gunner on a B-29 confessed to Los Angeles authorities that he was the Phantom; and while he was in Texarkana at the time of the crimes he was later cleared when his confession didn’t match up to what little evidence there was. But the prime suspect all along was a man named Youell Swinney. And maybe, just maybe, the Texarkana authorities had their man all along.

It was a 33-year-old rookie Arkansas State trooper by the name of Max Tackett who realized a car had been stolen on the nights of each attack. And while following up that lead, Tackett arrested Swinney and his wife, Peggy, who were in possession of one of those stolen cars. When arrested, Swinney begged Tackett not to shoot him. And when Tackett replied he wouldn’t shoot someone for stealing a car, Swinney answered, "Mister, don't play games with me. You want me for more than stealing cars." But the suspect sort of clammed up after that. His wife, however, wouldn’t shut up and gave a full detailed confession, implicating her husband as the Phantom; a confession she later recanted. And without the confession, or the wife’s testimony, with the lack of physical evidence, the District Attorney felt they couldn’t press charges on Swinney for the Phantom killings. But what they could do, and eventually did, was send the car thief to jail for a very long time as a habitual criminal.

Neither Gonzaullas or the authorities on the Texas side felt Swinney was really the Phantom. Whether this was to just save face, who knows. What we do know is the killings stopped after Swinney was caught. Still, the evidence was shaky and Swinney was later released early in 1973 on a technicality. But he was back in jail by 1975 for, you guessed it, stealing another car. Swinney was still alive and in jail when Pierce filmed The Town that Dreaded Sundown, which makes no mention of the car thief at all. Actor Andrew Prine always claimed he was the one who came up with and wrote the climax for Pierce’s version of the Phantom killer to give it at least some semblance of a resolution even though the killer’s identity is never resolved. This climactic shoot-out was a total fabrication. And it was Pierce’s wife who came up with the idea to have the Phantom attend the movie’s premiere to officially wrap things up, something John Carpenter would echo later at the end of Halloween (1978), where audiences had to leave the safety of the theater with the knowledge a killer was still at large.

Aside from all the dramatic liberties taken, which stretched the “based on a true story” conceit way past the factory specs, one of The Town that Dreaded Sundown’s most glaring flaws is it’s tonal inconsistencies, which were all Pierce’s fault both behind and in front of the camera as the worst offender is the odious comedy relief of patrolman, Sparkplug Benson, played by Pierce himself as an utter buffoon. (Think Officer Kelton in all those Ed Wood movies -- only dumber.) And what makes this so jarring is Pierce, his cinematographer, James Roberson, and stunt coordinator, Bud Davis, who also played the Phantom, execute these suspenseful murders so effectively, whose morbid impact is then completely lost when we cut to Sparkplug making an ass out of himself again AGAIN. And worst of all, you get the sense both the director Pierce AND actor Pierce thought this crap was actually funny.

On the other hand, aside from those hiccups, The Town that Dreaded Sundown is surprisingly effective on many levels. Most of the victims and bit parts were played by locals. Both Prine and Ben Johnson had worked with Pierce before and have good chemistry together -- both onscreen and off. And tales of those too whooping it up off-hours is a production story I would love to here sometime as apparently they were both so hungover while shooting the climax they could barely stand up. Dawn Wells was a last second replacement as the final victim; and believe me there is a weird dissonance when you see Mary Ann from Gilligan’s Island get shot in the face -- twice!

Being shot was a new experience for her as well: "They planted a charge in the receiver,” said Wells. “So I was standing there holding the phone, shaking, expecting the receiver to blow up in my face." Luckily it didn’t because what follows with her escape from the house and subsequent chase through the cornfield is a terrifying thing of beauty. But in the end, the film belongs to Bud Davis as the Phantom, even though we never see anything but his angry eyes and all we hear is his excited breathing, but the menace and rage he brings to each of his scenes are palpable.

Behind the camera, kudos to cinematographer Roberson, who shot the film with a broken foot, ruining two casts in the process. Roberson had shot Encounters with the Unknown for Thomason and would go on to shoot four films for Pierce. And while watching The Town that Dreaded Sundown, notice how Roberson utilizes the widescreen anamorphic Panavision lense so well and frames his scenes so right it rivals the work of Dean Cundey, who I feel is the master of the format.

Pierce also scored a coup when he struck up a friendship with composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava, which netted him a beautiful score for The Legend of Boggy Creek, which really helped glue that film together. Mendoza-Nava returned for The Town that Dreaded Sundown an concocted something even better; a haunting score with rural and rustic overtones that really helps to impend the dread. Also returning from Boggy Creek was Vern Steinman, who served as a narrator on both films. And while Sundown didn’t quite achieve the true documentarian vibe of Boggy Creek it had its own procedural vibe that served it well and got what Pierce was trying to get across effectively enough.

It took about four weeks of shooting during a very hot and rainy June in 1976 to complete filming of The Town that Dreaded Sundown. And after five months of post-production the film was picked up by American International Pictures and made its debut just after Christmas that bicentennial year. I vividly recall the TV commercials and radio ads for The Town that Dreaded Sundown and how they scared the ever-livin’ piss out of five year old me. I didn’t actually get to see it until years later as the bottom half of a “Based on a True Story” double-bill with The Amityville Horror (1979) sometime in the early 1980s. And of the two, I think Pierce’s film holds up way, way better.

When it was first released, Pierce had another huge hit on his hands. But despite his precautions, the filmmaker wound up facing several lawsuits. For while the city of Texarkana had been extremely cooperative during the production, they were none to happy with how the film turned out, especially how the otherwise stellar promotional materials claimed the killer was alive and well and still living in their fair city and sued to have any trace of this claim removed. And one of the victim’s relatives sued Pierce for invasion of privacy to the tune of $1.3 million over his fictionalized portrayal of Polly Ann Moore, Pierce was able to settle the first suit, and won the second when the case was tossed. And as the decades passed after the murders occurred and the film’s release, the city of Texarkana started to embrace their notorious piece of history, even engaging in an annual outdoor Halloween screening of Pierce’s film since 2003 in the very park where Martin and Booker were murdered.

Which leaves us with sorting out the legacy of The Town that Dreaded Sundown. As friend and fellow online film critic Scott Ashlin so eloquently put it in his review for 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting, “Like an artless hillbilly giallo, The Town that Dreaded Sundown is first and foremost a murder mystery in which it plain doesn’t matter whodunit.” And while I don’t think it’s completely artless -- the cinematography and the music will back me up on that, he does make a valid point about a film that goes, essentially, nowhere and resolves nothing.

This film is also often touted as a proto-slasher movie; and this has some merit when you consider the signature look of the killer, which was so fantastic it was later ripped off wholesale in Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981); and yet aside from the eccentric trombone attack and the cornfield chase, the killings are rather a blunt punctuation instead of the usual extended stalking as we spend little to no time with the victims. No frills, just sudden and intense explosions of violence executed so effectively you kinda wish the rest of the film would’ve lived up to these heinous murder set-pieces. And if that says more about the filmmaker or the viewer, well, that’s me shrugging right now.

What is Hubrisween? This is Hubrisween. And now, Boils and Ghouls, be sure to follow this linkage to keep track of the whole conglomeration of reviews for Hubrisween right here. Or you can always follow the collective head of knuckle on Letterboxd. That's 19 reviews down with 7 to go! Up Next: The X-Files it ain't, and 'the truth' is a load of pretentious bull-twaddle.

The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976) Charles B. Pierce Film Productions :: American International Pictures / EP: Samuel Z. Arkoff / P: Charles B. Pierce / D: Charles B. Pierce / W: Earl E. Smith / C: Jim Roberson / E: Tom Boutross / M: Jaime Mendoza-Nava / S: Ben Johnson, Andrew Prine, Dawn Wells, Jimmy Clem, Charles B. Pierce

No comments:

Post a Comment