Wednesday, October 14, 2020

Hubrisween 2020 :: I is for I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958)

After some outstanding orchestral maneuvers over an opening credit sequence that give us an approaching extraterrestrial’s POV of the planet Earth -- he typed ominously, we open in a town like any other town, USA, where the Sherman Tank-sized cars with the massive tail-fins clues us in that the Wayback Machine has deposited us sometime in the late 1950s.

We then enter a bar, where Bill Farrell's bachelor party is finally winding down. But as his buddies try to keep this party going just a little bit longer by buying one more round, Bill begs off, having promised to stop by and see Marge, his bride to be, on the way home. Seems their big day is tomorrow, bright and early. After he leaves, all the confirmed bachelors around the table say they would rather kill themselves then commit to marriage. And those who already took the plunge, well, there’s a reason they wanted to keep the party going so they wouldn’t have to go home to you know who.

Later, while winding his way home, an intoxicated Bill (Tryon) spots a body lying in the middle of the road too late after rounding a blind corner. Slamming on the breaks, his car screeches to a halt with a sickening thump. But when he gets out to check on whomever he hit, Bill finds the body has disappeared. Knowing he's had way too much to drink, Bill is about to chalk this up to the Pink Elephant Brigade until he turns to leave and a very monstrous, phosphorescent three-fingered hand -- nearly tentacles, grabs him from behind.

Spinning to face his attacker, the man recoils in terror at what he sees: an alien, who has a basic humanoid shape, with thick, rubbery skin, no visible nose, two large eyes set deep underneath a huge cranial protrusion, its puckered mouth covered with some form of breathing apparatus, and four very large arterial shunts that run from its head directly into its chest and shoulders. And not only does this thing glow, but it also produces a strange and menacing drone. All of this proves too much for poor Bill, who collapses into unconsciousness. And as the alien hovers above him, who baited this apparent trap, a thick black fog quickly envelops his victim's prostrate form; and then, when the smoke just as rapidly dissipates, Bill’s body is gone. Alive or dead, no one can say.

Thus, when the groom fails to show up at the church the following day, a distressed and needling toward pissed-off bridezilla-to-be Marge (Talbott) starts grilling all of the groomsmen, wanting to know what they did to her fiance at that bachelor party last night. (Apparently, he also failed to stop by like he said he would.) But just before heads start rolling, Bill finally shows up, safe and sound, with no apparent memory of what happened to him the night before. And as the couple shares a make-up kiss, Marge’s mother pulls them apart, saying to save some of that passion for later -- they’re going to need it.

After the ceremony, the newlyweds take off on their honeymoon. But along the way to the hotel, Bill almost causes a wreck by driving at night with his headlights off. He also becomes very defensive when Marge, who’d been napping, asks how he’d managed to get so far in the dark. The new bride is even more puzzled after they reach their beach-side destination and Bill basically forgets her in the car, and then becomes a little miffed when her husband also neglects to carry her over the threshold of their honeymoon hideaway as tradition holds.

And as the evening progresses, Bill's behavior grows even more distant and bizarre, acting like he’s never seen a thunderstorm before, and he won’t even touch the champagne. Hoping it’s all just marital jitters, Marge heads inside just as a lightning flash reveals that alien’s horrible visage hidden underneath Bill’s features, which confirms our suspicions that Bill wasn't really Bill at all! And then Marge, who didn’t see any of this, calls her new husband into the bed for one last wedding night tradition, with no idea of whom -- or what, she is about to sleep with as we fade to black...

As a reporter for The Denver Post, one of Gene Fowler’s plum assignments was to interview the legendary Buffalo Bill Cody when his Wild West Show rolled into town. But instead of asking him about the tenets of this traveling circus, Fowler instead grilled Cody over his many illicit love affairs. (There was a persistent rumor/joke that Fowler was the illegitimate son of Cody, explaining the rancor.) And it was this kind of brazen behavior and impertinence that soon became the reporter’s trademark as he moved to New York City, where he worked for The Daily Mirror before shifting to a management position for the King Features Syndicate. Around 1930, Fowler began writing for the stage and the cinema -- What Price Hollywood? (1932), The Call of the Wild (1935), as well as several books, including biographies and memoirs for the likes of P.T. Barnum and Jimmy Durante.

After a move to Los Angeles, Fowler Sr. rubbed elbows and became close friends with many of Hollywood’s current elite, including John Barrymore and W.C. Fields, who legendarily despised all children, except for Fowler’s sons, which the irascible Fields claimed were the only children he could stand. And it was while writing his latest book, Father Goose, which chronicled the career of seminal silent filmmaker Mack Sennett, where Fowler introduced his eldest son, Gene Fowler Jr., to Allen McNeil, one of Sennet’s film editors. Well, McNeil and Fowler Jr. also hit it off, which resulted in a job offer to also become an editor at 20th Century Fox. (Editor's note: From here on out, when we refer to Fowler we are referring to Fowler Jr.)

Fowler’s first feature was an uncredited assist for McNeil on Roy Del Ruth’s screwball musical, Thanks a Million (1935). And after a few more assistant editing gigs on the likes of Western Union (1941) and Weekend in Havana (1941), Fowler’s big break came when he was chosen to edit a couple of Fritz Lang’s suspense yarns, Hangmen Also Die (1942) and The Woman in the Window (1944), where he struck up a lifelong friendship with the noted director and constantly picked his brain. “The man knew how to move a camera,” Fowler said in a later interview with Tom Weaver in Science Fiction Stars and Horror Heroes. Seemed Fowler had bigger ambitions outside the editing room.

But Fowler would get his first tour in the director’s chair on the small screen, shooting and editing multiple episodes of China Smith, which featured Dan Duryea as a less than honest private detective, running scams and eking out a living in post-war Singapore, with San Francisco’s Chinatown serving as a reasonable facsimile of the far East. Fowler would continue in that capacity for The New Adventures of China Smith, as well as editing The Abbott and Costello Show and Rocky Jones, Space Ranger. But Fowler was still editing features, too, doing the cutting on Lang’s While the City Sleeps (1956) and a trio of films for Samuel Fuller, China Gate (1957), Run of the Arrow (1957), and Forty Guns (1957).

It was mere happenstance that Fowler crossed paths with producer Herman Cohen, whose latest production just so happened to occupy the editing suite right next to his while Fowler was stitching Run of the Arrow together. The two got to talking, became friends, and then one day Cohen approached Fowler and asked if he’d like to direct a movie for him. Fowler was eager to get his first feature, but Cohen was very diplomatic upfront, saying the project had the worst title but the script was decent enough. He then handed it over for Fowler to read, who almost backed out on the spot when he saw what was written on the cover page.

Deciding to at least give it a read, Fowler took it home but still wasn’t sold until his wife convinced him to do the feature, get the needed experience, and not to worry because odds were good nobody would ever go to see something called I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957). “There were a bunch of these exploitation pictures being made, but at the time there didn’t seem to be a very big market for them,” Fowler told Weaver in the same interview. “I guess the other producers must have been spending just about the same amount of money that we were, but their pictures were such shit. I did not try to make just an exploitation picture. I was trying to do something with a little substance to it."

And while Fowler felt Aben Kendel’s script was fair enough, he added a lot of rewrites on Teenage Werewolf, adding a few things here and there to flesh out the characters -- most notably the film’s true villain, Dr. Brandon, who, as written, was nothing more than a stereotypical, raving mad scientist. “I always figured that a villain, in his own eyes, was a very good, very nice fellow,” said Fowler. “ So I tried to make the villain that way -- he was actually trying to do good for the world. I tried to get some sympathy for him, or at least some understanding. I remember talking to Whit Bissell, who played the doctor, and telling him, ‘Keep in mind you’re not a bad man.’"

Heeding the advice of his mentor, Fritz Lang, to always be prepared and then adapt accordingly, Fowler was ready, adaptable, and able, completing the picture in just six days and on budget ($82,000). Fowler’s German Shepherd, Anna, wound up in the film, too, as the dog the Teenage Werewolf kills. It would not be her last screen roll either.

When he was hired on, Cohen offered Fowler a percentage on the film or a straight salary. Fowler chose the salary, feeling with a title like that the film would quickly disappear, which turned out to be a huge mistake because due to his own outstanding efforts and American International Picture’s crack publicity team, I Was a Teenage Werewolf was a huge hit, grossing over $6-million on its initial run, and spawned a franchise -- I Was Teenage Frankenstein (1957), Blood of Dracula (1957), and How to Make a Monster (1958). When asked why he didn’t stick with Cohen and AIP, Fowler admitted while he enjoyed the familial experience there, he didn’t want to get stereotyped and, in the end, was looking for something a little more stable.

And this he found by signing on with Robert Lippert, who had just cut a deal at Fowler’s old stomping grounds, where the producer agreed to make a ton of second features for 20th Century Fox in their new CinemaScope format for his Regal Pictures. Here, Fowler was assigned a partner in screenwriter Louis Vittes. Vittes had only been in the business since 1955 and only recently migrated from television to feature films with Monster from Green Hell (1957) for Al Zimbalist and George Waggner’s Pawnee (1957) before he, too, hired on with Lippert.

And together, these two would scour the back-lots of Fox and frame entire features around whatever sets were leftover from any bigger productions, resulting in a western, Showdown at Boot Hill (1958), a crime picture, Gang War (1958), and a war film, Here Come the Jets (1959). Here, they had better production values and a little more money to spend than he had for Teenage Werewolf -- $125,000 per picture, but Lippert was no less a tightwad and a stickler for staying on budget, which is why Fowler once had to trade 30 Indian extras to get a crane shot he desperately needed for The Oregon Trail (1959). For if a Lippert picture went over budget, the director had to cover the cost of the overages out of his own pocket. But if it came in for less than the designated amount, only Lippert would pocket the difference.

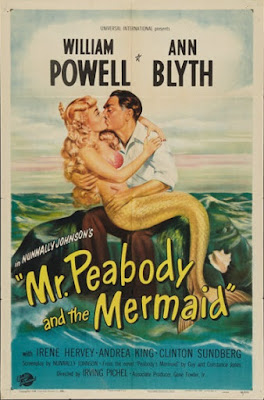

Thus and so, seeing where the money was really being made, Fowler started entertaining the notion of producing his own low-budget feature. He had already served as an associate producer back in the 1940s on The Senator Was Indiscreet (1947), and on one of the greatest representations of a mid-life crisis ever put to film with Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid (1949). (Seriously. It’s my favorite William Powell movie. Check it, Boils and Ghouls.)

Teaming up with Vittes again, Fowler called on his experiences working with Cohen, AIP, and even Lippert, as the two men came up with an outlandish title to sell first, and then hammered out a script to fit it from there. And what they concocted was perhaps the most outlandish exploitation title ever conceived for a film: I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958). (Well, at least until Ray Dennis Steckler came along.) As for the script that went with it? Well, as Fowler said about the making of the picture, “We were certainly capable of coming up with a [better title]!” But, “One of the things I’ve always found is that you’ve got to accept the premise, regardless of how ridiculous it is. If you accept the thing as very realistic and very honest, then you can come up with very honest performances and make a fairly honest picture out of it."

And the honest to god premise Fowler and Vittes’ cooked up for I Married a Monster from Outer Space was very, very sobering, indeed, as the last surviving members of an ancient alien race clandestinely come to Earth to try and save their species from extinction. We’ve already seen how, but as to why, well, we’ll continue to unravel that mystery as we go.

Meantime, their protagonist, Marge Farrell, still doesn’t realize this switch has happened yet, even though a whole year has passed since she and Alien Bill tied the knot. However, that doesn’t mean she hasn’t had any suspicions about the drastic behavioral changes in her husband. Marge is no fool. But the problem is, and it’s the true focal point of this film as far as I’m concerned, Marge cannot get anyone to listen or believe her when she claims Bill is no longer himself.

Sure, Bill’s friends miss their old drinking buddy, too. Speaking of, one of those diehard bachelors, Sam Benson (Dexter), barely survives last call at the same watering hole. And as he stumbles his way home on foot, all that liquor in his gut suddenly revolts, causing him to duck into an alley. But between heaves, this purging is interrupted when another alien attacks and assimilates him, too. It’s been a year, remember, so who knows how many “real” men are actually left in this town.

To add another layer of tension to this dire situation, even though they’ve been trying since day one, Marge and Bill still haven't successfully conceived yet. And the only emotion she can consistently get out of Bill is an all-consuming disappointment over this failure to, well, launch. Thus, a worried Marge makes an appointment with her doctor. And when he can’t find anything physically wrong that would prevent her from having a baby, Dr. Wayne (Lynch) concludes Bill might be the problem and would like him to come in for a check-up, too.

On the way home, Marge runs into Benson (-- and we know he’s been successfully assimilated because it's the middle of the day and he’s still sober), who makes the surprise announcement that he and Helen Rhodes (Carson), his long suffering girlfriend, just got engaged. Later, Marge returns home with a surprise of her own: she’s bought them a little dog for their anniversary. But when the pup gets one whiff of Alien Bill, it goes berserk. Strange, says Marge. It was just fine and friendly at the pet store.

Here, Bill makes up an excuse to keep the dog chained in the basement until it warms up to him. But whenever Bill tries to make peace with the animal, the dog will have none of it. And so, with no other choice, Bill picks up a hammer (-- nope, too messy), but quickly discards it. He’ll just have to get his hands dirty on this one. Thus and suddenly, the house is filled with the sounds of a dog in terminal distress. Rushing to the basement, Marge is stopped at the entrance by her husband, who claims the dog somehow strangled itself with its own leash.

Once the poor dog is removed and buried in the backyard, Marge finally gets around to telling Bill about her doctor’s appointment, and how Dr. Wayne couldn’t find anything wrong with her. His detached reaction to this news isn’t what she had hoped for, but was expected. And here, Marge makes a little Freudian slip when she accuses her husband of acting like an evil twin sometimes. Urged to see the doctor so they can get to the bottom of things, Bill is apprehensive but agrees -- mostly to appease her, which is about to trigger another fight when the doorbell rings, providing Alien Bill a much needed distraction.

It's Sam Benson; and after Marge excuses herself so these two men can talk men’s business in private, Benson reveals he’s also a doppelganger, and then openly complains about the model of human he got stuck with (-- that’s why you should always kick the tires first, bub). With that, they quiz each other over the mistakes they've made so far, and how their overall, byzantine master plan is still proceeding without a hitch for they have now managed to take over every key citizen in town and are almost finished replacing all of the local police force.

Before leaving, Benson reminds Bill that his methane supply is dangerously low and will need to be replenished soon. And so, later that night, thinking Marge is asleep, Bill sneaks out of the house. But Marge was only playing ‘possum, and then quietly follows her husband deep into the woods until he reaches a secluded gully. Sadly, Alien Bill wasn’t that hard to track; all Marge had to do was just follow the trail of dead pets. (You wish I was kidding.) Staying hidden, Marge spies a strange ship hidden behind the trees. And when Bill stops in front of it, that same black fog seeps from his body and then reforms into a big, squishy alien.

Once safely extracted, the alien leaves Bill outside and enters the ship. Feeling they’re now alone, Marge calls out to her husband and then runs to him when he doesn’t respond. Barely touched, Bill falls over, stiff as a board, making this simulacrum essentially nothing but an empty shell. Horrified, the woman watches as a large bug crawls across Bill’s unflinching face; and as all of this slowly sinks in -- what has happened to her husband, and what’s she’s been having sex with for the last year, and finally clicks into place, Marge unleashes one helluva scream as she turns and flees, trying to desperately run away from the truth, all of it, as phantasmagorical images of that monster plague and torment her all the way back into town.

Once there, the only place still open at this hour is the bar, but no one there will believe her. She tries the police next, demanding to see Chief Collins (Eldredge), who also just happens to be her godfather. Surely he will believe her, right? Well, while Collins does listen to her fantastic story and assures the girl she’s not insane, maybe a little hysterical, sure, he doesn’t really do anything except promise to follow up on all of these out of this world accusations. Collins then tells Marge it would be best if she went home because if Bill really was an alien, he mustn't suspect anything or tip their hand until he completes his investigation, confirms the location of the UFO, and contacts the federal authorities who handle such matters.

Reluctantly, Marge agrees to all of this, but after she leaves a lightning flash reveals Collins has been taken over, too. Returning home, Bill is there waiting, seemingly none the wiser. Making up some excuse for where she’s been, Marge holds it together and heads to bed.

More time passes, and we pick things up at Sam and Helen’s wedding rehearsal. Taking Helen aside, suspecting Sam has also been replaced, a nervous Marge encourages her friend to postpone the wedding but refuses to say why. Then, Bill interrupts them before Marge can take it any further. Later that night, ready to get all of this out in the open, Marge starts to pull on a few threads, asking Bill why he never drinks anymore? This kind of opens the floodgates a bit but the wily Alien Bill quickly turns the tables and accuses her of changing, too, these past few weeks. This reverse psychology appears to work as a despondent Marge gives up, claiming she’s tired, and leaves the room.

Frustrated, Alien Bill breaks the glass held in his hand. He then spots someone spying on him and sends out a psychic SOS to his alien comrades, who quickly catch the man -- whom we recognize as one of the men Marge talked to at the bar. He confesses to all of this but, apparently, he didn’t believe anything she’d said. He just figured the Farrell’s marriage was on the rocks and wanted to scope out the possibility of catching Marge on the rebound. But I’m thinking he believes in those aliens now -- now that it’s too late. Still, he makes a fight of it, drawing a pistol and opening fire. When these spent bullets have no effect, Alien Bill watches from the house as the Alien Cops finish him off with their own commandeered terrestrial weapons. Moving into the bedroom, Alien Bill assures Marge all she heard was a car engine back-firing. He then tries to apologize for the whole evening but she's too upset; and so, as a peace offering, he offers to sleep in the guest room until she’s ready to talk.

Several days later, Bill joins a few other alien doppelgangers at the bar. As they quietly discuss their invasion's progression, we finally discover exactly what their endgame is: compatible breeding stock. However, there is a continued delay because their scientists are still unable to make the alien chromosomes compatible with a human’s. And until they do, they’ll just have to mark time. But they’ll have to do that someplace else from now on after the bartender kicks them out for wasting his time and liquor.

Meantime, down the street, the town floozy (Allen) spots another possible mark looking in a department-store window, freshens her makeup, and saunters on over. (Sharp ears will pick up the alien’s naturally occurring drone, so methinks she’s in trouble.) Ignored completely, the woman gets mad and pushes him.

And when the hooded figure turns to face her, revealing an alien underneath the hooded jacket, the startled hooker screams and runs away. Raising a weapon, the alien fires some kind of disintegrator beam -- for in a fiery flash, the town’s population suddenly decreases by one. Turning back to the window, the creature's distorted features ominously reflect off the glass near a baby doll display.

The next day, the Farrells join Ted and Carolyn Hanks (Wassil, Fields) for a lakeside picnic in the park. But just as they spot Sam and Helen Benson out on the water, Sam falls overboard. When he doesn’t surface, Ted, whom we know is still human because his wife is pregnant, quickly jumps into the water while Bill lingers near the edge. (Strange behavior, since Bill used to be a strong swimmer -- stressed on the used to be.) Hauled to shore just as Dr. Wayne arrives, Sam appears to recover until he is given some forced oxygen, goes into convulsions, and then expires. And if he didn’t know any better, Dr. Wayne would swear the oxygen appeared to be the cause of death, which doesn’t make any sense. Thus, the normal people in the gathering crowd are equally perplexed, while the alien doppelgangers sit apart in concerned silence.

Since he's done precisely diddly and squat since their last meeting, Marge seeks out Collins again, who this time advises her to drop all this alien business or she’s liable to wind up in the loony-bin. Sensing the conspiracy is growing, she tries to call the federal authorities on her own but can’t get through, and when she tries to send a telegram, as she leaves, Marge notices the clerk tearing up her message and throwing it away. The girl even tries to leave town but the police have the main road blocked, claiming it's been washed out.

Frustrated at every turn, Marge returns home, where she sits and stews in the dark. When Bill offers to turn on the lights, she tells him not to bother; he doesn't need them anyway, right? Here, Bill waits for a pregnant beat and then asks what she knows. Told she knows everything, Bill decides to spill it all and reveals the plight of his people:

They come from the Andromeda Galaxy, escaping their planet on space-arks when their sun went supernova. But they weren't quite fast enough, and the resulting radiation killed off all of their females, meaning their race is doomed unless they can find a suitable replacement. That’s why they’re on Earth, trying to assimilate their way in. But something’s gone wrong with their great plan: human emotions are starting to assert themselves in the alien hosts. (Ah, the horrors of Ro-Man’s Syndrome strike again! What’s that, you ask? Stay tuned until we get to the R-entry and all will be explained.) When Marge asks if they know what love is, he says no, they have no concept of it, but insists he is starting to learn. He then drops the bomb that, eventually, they will get over this genetic hump and have children with Earth women -- including her.

Trapped and seeming all alone, Marge turns to Doctor Wayne again, and luckily, they haven’t gotten to him yet. And after putting her story together with what happened to Sam Benson, he starts to believe her tale of alien doubles. Unable to go to the police, they don’t know where to turn for help, when suddenly, Ted Hanks breaks in, announcing that Carolyn just gave birth to twins. With that, Wayne now knows where to get the help they need and sends Marge home to keep Alien Bill from getting suspicious. Dr. Wayne then grabs Ted and heads to the waiting room for the other expectant fathers.

Once back at the Farrell residence, Bill quickly deduces Marge has finally found some help and his mission is in danger. He then receives a psychic SOS from the base ship and leaves her to go and help his comrades. Rounding up those alien patrolmen, they head into the woods with Marge right behind them.

Well ahead of them all, Dr. Wayne, who managed to round up a sizable armed posse of new fathers, has reached the spot where Marge said the spaceship was hidden. Find it they do; and when the hatch opens and two glowing aliens emerge, armed with those disintegrators, a man with a pair of German Shepherds leads the charge.

As a firefight erupts, the human’s bullets have no effect while one of the aliens blasts the dog-handler into oblivion. But his dogs attack the other sentry, savaging it fiercely.

And as the monster screams in pain, the dogs tear through those exposed arteries, causing it to quickly bleed to death. (That one was for Sparky, who died in the basement!) The second alien then disintegrates one of the dogs, not realizing that the other canine was getting the drop on him. And then Fido (Anna) makes quick work of him, too. (That one was for Mittens the cat, who died in the alley!)

Both alien bodies quickly dissolve (-- rather messily), and the Earthmen cautiously make their way toward the opened saucer. Inside, they find several humans suspended in some kind of force-field. (Including Bill, Sam, Collins, and all of the policemen.) Dr. Wayne isn’t sure what to make of the alien technology but concludes they have no choice and just starts pulling the plugs on all the machines -- while crossing his fingers and hoping he doesn’t kill anybody.

Outside, as Alien Bill and the patrolmen run toward the ship, one of the cops screams as his Earth counterpart is unplugged; the doppelganger then falls and violently dissolves into a puddle of translucent goo, leaving the other two to press on alone.

Back at the ship, when Chief Collins is unplugged, the Alien Collins at the station radios the Andromedan fleet and reports all is lost. But before he collapses and discorporates, he orders them to destroy the scout ship and abort the mission, and then promptly disintegrates (-- in several disgusting blorps). Meanwhile, as the rescuers start moving the recovered humans outside the ship, about a dozen in all, Dr. Wayne keeps freeing the others still trapped inside.

Unplugging the second patrolmen, his alien double screams in agony. Putting him out of his misery, Bill stops and disintegrates him before he can dissolve. This allows Marge to catch up, giving the alien a chance to plead his case to her for one last time.

In the end, he wishes Marge had never found out the truth; and when the real Bill is unplugged, Alien Bill tells Marge to look away. And as he collapses and writhes in agony, she does look away -- but we, being the Sick-Os that we are, morbidly watch as Alien Bill spreads out all over the ground. (Blorp-blorp-blorp...)

The real Bill was the last one pulled out, and since the spaceship is making a funny noise, that's getting louder by the second, they evacuate the area. Once everyone is clear, the ship explodes, Marge and Bill are reunited, and it appears that they’ll live happily ever after as we pan-swipe back to outer-space and see the Andromedan fleet pulling away from the Earth and depart into the unknown.

In that same interview with Fowler, Weaver points out how, in nearly every positive review of I Married a Monster from Outer Space, the writer always goes out of their way to apologize for the title while trying to defend the movie. And I guess I kinda agree with this assessment, and will even echo it to a point, even though I think it’s a kooky title that rightfully belongs in the Hall of Fame of such things. Great film. Kooky title, which kinda betrays some pretty heavy overtones of sexism, paranoid themes, and multiple layers to sift through if a viewer so chooses; or, you can take it face value as there are enough shock moments, mass disintegrations, and gooey alien deaths to keep everybody happy.

Fowler’s film also makes a nice bookend for an alien invasion trilogy that started with William Cameron Menzies’ Invaders from Mars (1953), then continued with Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), and then ending with I Married a Monster from Outer Space. All dealt with the same notions of aliens coming to Earth and secretly assimilating their way to conquest; with Menzies giving us the kids view, Siegel the male, and Fowler the female -- and an argument could also be made that we get the invaders point of view, too, as a good portion of the film is dedicated to Alien Bill and the Andromedans’ unfolding plans.

A secret invasion, a growing conspiracy, and roiling paranoia of not knowing who to trust, of course, also means that I Married a Monster, as a product of its era, must also be lumped into the category of Red Menace metaphors. And while the correlations are easy enough to make, I honestly think the main villain of this film is not some politically charged alien invasion but an all-encompassing fear of equality and commitment -- not Communism, and a terrible aversion to getting married. Much venom is spouted in Vittes screenplay by the unrepentant bachelors against the very institution of marriage -- one even claims he’d rather commit suicide than get hitched, which is only equaled by those who took the plunge and have regrets. And so, the only person who really wants to be in a committed relationship is Alien Bill. But, he has an ulterior motive, remember.

“This was strictly an exploitation picture,” said Fowler. “But there again, I tried to put characterization into the monsters. The so-called monsters, the aliens, were a very sad people … And this premise was kind of sad: these aliens, all of their women had died off, and they were searching the galaxy for women to propagate their race. They were desperate. What they were doing, as far as they were concerned, was very honest and very necessary."

And they also tried to do this as painlessly as possible. Notice how the Andromedan cross-breeding plan would’ve been a helluva lot easier through a mass abduction and experimentation from the safety of their fleet -- like in the later film, Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster (1965). Instead, they come up with an elaborate subterfuge. Was their plan to stay here and just assimilate their way in and keep the species alive? And then take over? Or once these genetic hiccups were resolved, would they take their viable offspring and move on? Who can say for sure. It also makes you wonder if all the bawdy innuendo and implied sex between Marge and Alien Bill was allowed by the censors only because Bill was an alien?

But this also opens up a whole ‘nother can of worms because Marge’s treatment at the hands of all the males in this film is pretty horrific. As I mentioned earlier, it says a lot that no one will believe her or simply writes her accusations off as nothing more than hysteria -- read, raging hormones. And whether it be in service to terrestrial or extraterrestrial, Marge and all the other women are to know their place, be seen, not heard, and their entire purpose in life is nothing more than to make babies to propagate the species. No more. No less. Note how the only human casualty in the film before the climax is the hooker, who uses sex for something other than propagation and is therefore expendable.

As to whom Marge would be better off with, Bill or Alien Bill? Who can say for sure despite the apparent happy reunion at the conclusion. But do we really know what the real Bill was really like? Sure, Alien Bill can tap into his memories through their machines -- whose signals get interrupted whenever there’s an electrical storm, but he never really exploits this properly. And by the time he mentions that he’s learning about what we humans call love, it’s already too late. But I’ve often wondered sometimes if the film had been scripted by, say, Rod Serling, or William Gaines, we’d have an epilogue, perhaps another year later, where we find out that Bill is an abusive, raging alcoholic and Marge still can’t escape this domestic hell. And think about poor Helen, too, when she not only realizes her husband wasn't dead but never wanted to get married in the first place?

Tom Tryon and Gloria Talbott had worked together before a year earlier on the supernatural-tinged Dark of the Moon episode of the anthology TV-series, Matinee Theater, where they play another mismatched couple -- he’s a powerful warlock, she’s a mortal, whose relationship ends in tragedy. Here, they struggled to find some chemistry but I honestly think this unease actually helped the production given the doppelganger plot and how these two essentially become complete strangers. Tryon was just starting to get some traction in his career and honestly wanted no part in making this kind of movie but was contractually obligated. Most reviews point out how wooden his performance is, but was this on purpose? The guy really was into the burgeoning method movement after all.

On the other hand, Talbott was a genre veteran by now having starred in The Cyclops (1957) and The Daughter of Dr. Jekyll (1957). Always a trooper, Talbott would do all that was asked of her and brings a certain grit and realness to Marge, even though she was plagued throughout the production by an abscessed tooth. And her only real complaint was with Vittes, who was so pathological about his dialogue he hung around the set, mouthing his words while the actors spoke them, and would throw a fit if they ever deviated from the script, allowing no improvisations or improvements, causing some tension until Fowler stepped in and had him removed.

As for those alien menaces, they were conceived by Fowler and then built and brought to life by the great Charlie Gemora, who was a noted Hollywood Gorilla-Man, and who had also designed the tri-optic Martians for Byron Haskin’s adaptation for The War of the Worlds (1953). “I designed those monsters,” said Fowler. “And I designed them with only one thing in mind: so I could get rid of the god-damned things. I gave them a vulnerable spot, those tubes on the outside of their bodies, which gave the dogs something to get a hold of."

The production’s budget allowed for the creation of two monster suits -- worn by Gemora and stuntman Joe Gray, who wound up having to wear pants as dictated by a studio mandate. Originally, it was merely some kind of cosmic jockstrap that brought jeers from the cast and was quickly swapped out with a longer set of trousers. To complete the films FX, Fowler turned to optical specialist, John Fulton, who had been doing this kind of thing since his days at Universal in the 1930s, where he worked on damned near all the monster franchises -- matte paintings for Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931), optical tricks for The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and Werewolf of London (1935) and kept at it through House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945). Here, he added in the transitional smoke effects, the alien’s illumination, the superimposed faces, and the goop for their rather messy demise.

The film was shot in glorious black and white, allowing Fowler and cinematographer Haskell Boggs to give I Married a Monster from Outer Space a rather cool, noirish flare -- epitomized by the constant scenes of Bill lurking in the shadows, spying on Marge, who is always brightly lit, that are extremely effective. They also make excellent use of shadows, and a lack of lighting, and I love how it always seems to be raining or a threat of a thunderstorm, which produces the film’s greatest shock moment. And editing all of this together was George Tomasini, who was the cutter for some of Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest films -- Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), and The Birds (1963). So, he knew what he was doing. And even though his background was in editing, Fowler’s philosophy was to let his editors be and do their own thing, which was good as Tomasini really rings all kinds of tension out of this potboiler.

It was Paramount who wound up financing and distributing I Married a Monster from Outer Space, and it was shot mostly on their lot. When it was finished, it was paired up with Jack H. Harris’ independently produced The Blob (1958), which was quickly switched to the top of the bill because it was both in color and proved more popular. Learning his lesson on I Was a Teenage Werewolf, Fowler negotiated for 25% of the film’s profits as part of his salary but, like so many others, he was cheated out of his fair share when Paramount cooked the books to maximize their own profits.

Sadly, Fowler would only direct three more features after I Married a Monster from Outer Space before his phone stopped ringing. Seems he somehow made it onto the unofficial greylist over a petty dispute concerning the rights of Clair Huffaker’s novel, Flaming Lance, which was eventually adapted into the Elvis Presley vehicle, Flaming Star (1960). But Fowler did continue to direct on the small screen until 1961, and then continued to edit film and TV well into the 1980s. And while his opportunity was limited to just nine films, two are bona fide classics and are case studies in never judging a film by their absurd titles alone.

Well, if you don't know what Hubrisween is by now, Boils and Ghouls, I don't think I can help you. Anyhoo, that's NINE films down with 17 yet to go. Up next, Just When You Thought it Was Safe to Go Back to SeaWorld...

I Married a Monster from Outer Space (1958) Paramount Pictures / P: Gene Fowler Jr. / D: Gene Fowler Jr. / W: Louis Vittes / C: Haskell Boggs / E: George Tomasini / M: Franz Waxman / S: Tom Tryon, Gloria Talbott, Robert Ivers, Chuck Wassil, Valerie Allen, Ken Lynch, John Eldredge, Alan Dexter, Jean Carson, Darlene Field

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment