We open with a brief history lesson, where we learn that in this timeline, shortly before the start of World War II, the German High Command began an extensive covert operation to investigate further into the occult and the supernatural, focusing on the ancient Teutonic folklore that told of a race of warriors who used neither weapons nor shields, and whose preternatural powers were supposedly drawn from within the Earth itself.

And as war finally broke out, quickly escalated, and then turned against Germany, caught between the Allies and the Russian Army, the Nazi Schutzstaffel (better known as the SS) secretly recruited a group of scientists to create an invincible soldier to help turn the tide, who began experimenting on the bodies of those killed in battle. Thus, in a secret laboratory near Koblenz, these cadavers were used in a variety of … experiments.

Now, as this history lesson ends, it’s long been rumored that as the Third Reich collapsed, and Germany’s borders were breached, Allied forces started encountering fanatical terror squads that fought ferociously with no weapons and killed only with their bare hands. No one knows who or what they were, where they came from, or what became of them after Germany finally surrendered. But one thing was for certain: of all the German SS units, there was only one the Allies never captured a single member of.

Next, we cut to the present day (circa 1977) somewhere in the waters just off the Bahamas, where a local fisherman and his son find a small boat cast adrift on the open sea. Finding only one lone occupant, a woman, parched and sunburned, slipping in and out of consciousness, the fisherman brings her aboard his own boat, treats her as best he can, and asks how she came to be in such a predicament as they putter back to the harbor and proper medical care. Slowly, this obviously traumatized and delirious woman tries to come around, and then starts to relate her harrowing and unbelievable tale of woe and terror:

Our survivor’s name is Rose (Adams), and as her flashback begins we once more find the girl in the water -- sans boat, having a relaxing swim in the clear blue Caribbean water. One of four passengers booked aboard the Bonaventure -- a small chartered cabin-cruiser, which has, for the second time in as many days, developed engine trouble, Rose took the opportunity for a refreshing swim while waiting out the repairs.

Meanwhile, the Bonaventure’s curmudgeonly skipper, Captain Ben Morris (Carradine), is giving his first mate, Keith (Haplin), all kinds of hell on both his mechanical skills and navigational abilities. But as the engine begrudgingly groans back to life, unbeknownst to our pleasure cruisers, something sinister is afoot just beneath the waves several leagues away -- well, if the sudden ominous music sting is to be believed.

But this change in tone is somewhat confirmed -- or at least reinforced, when we spy a half-sunken freighter lurking nearby; and judging by all the corrosion, it appears to have been there for awhile. But if you listen close, somewhere below the waterline, you can hear some kind of rhythmic pounding; almost as if something was stuck inside this rusted-out hulk, something that was desperately trying to get out.

Then, the afternoon sky suddenly shifts to a deadly shade of Orange Fizz, causing the ship’s radio and compass to go on the fritz (-- making me believe they’re somewhere in the dreaded Bermuda Triangle, though the movie never confirms this). Here, stating the obvious, Captain Ben orders Keith to get them the hell out of there -- and fast.

Later, once the old tub is clear of the ethereal light show, we finally get around to meeting the rest of the passengers as they gather in the galley and wait for Dobbs (Stout), the ship’s slovenly cook and only other hand, to bring out the food. Here, Norman (Davidson, a dead-ringer for Buck Henry), once again complains to Captain Ben about the derelict condition of his boat, which was oversold a bit in the brochure, I’m guessing. And when you couple the mechanical failures with all the other strange things going on, the surly passenger demands to be returned to port, any port, before they inevitably sink.

And as her husband continues to rant, all Norman’s wife, Beverly (Sidney), can do is roll her eyes in a long-suffering fashion, just as the Old Salt snaps back, asking what a used car-salesman from Cleveland would know about boats anyway, entrenching both the skipper’s and Norman’s assholishness even further (-- so much so, I’d be surprised if either of them made it past the second reel.)

But then Chuck (Buch), another passenger, interrupts them, wanting to ask the captain for his opinion on all those strange lights in the sky and the tales of ghost ships and sea monsters that Dobbs has been filling these land-lubbers heads with ever since they first cast off. Told in no uncertain terms that Dobbs is completely full of shit, Captain Ben excuses himself. Once he’s gone, Norman’s call for a mutiny is quickly laughed off by the other passengers.

Later that evening, while everyone else sleeps, Rose visits the bridge for a smoke, where Keith is standing watch. And as these two get to talking, Keith admits that for all intents and purposes the Bonaventure is hopelessly lost; and with all of their electronic equipment no longer working, and the damnable compass still moving in a wobbly circle, this dire situation is unlikely to remedy itself anytime soon. And as if this situation weren’t bad enough already, suddenly, a ghostly freighter appears out of the darkness on a direct collision course!

But Keith takes the wheel and manages to minimize the impact as the rogue freighter only scrapes the side of the Bonaventure -- but it's enough of a jolt to wake everyone else up. But by the time the rest all get topside, the phantom freighter has up and disappeared, explaining why Captain Ben doesn’t believe Keith or Rose and figures his idiot underling fell asleep at the wheel and ran them aground.

Shooting off a flare to assess the damage, the phosphorescent glow illuminates that half-sunken derelict off the starboard bow. (Or maybe the port side? That’s me shrugging, as I know less about boats than a used car salesman from Cleveland.) That couldn’t be the boat that hit them? Could it? (Cue the Twilight Zone music!)

As day breaks, the others soon realize that Captain Ben has disappeared. All they can find of him are his discarded clothes (-- which means, wherever he is, John Carradine is buck-ass naked! Noodle that for a bit, Boils and Ghouls!) And as the rest of the crew checks for damage, they confirm that last night’s eerie close encounter finds them stuck on a reef. Worse yet, the bottom of the boat has been split open, meaning when the tide comes in the Bonaventure will definitely capsize and sink.

With no other recourse, the decision is made to abandon ship and start ferrying the passengers over to a nearby island with the Bonaventure’s dinghy, which is so small it will require several trips. Thus, while bringing the last load over, the unlucky passengers finally find Captain Ben -- through the glass porthole in the bottom of the boat as he floats by, drowned and definitely dead.

Once everyone else is safely ashore, Chuck climbs a tree, gets the lay of the land, and is happily surprised to spot some buildings about a half-a-mile inland. And after making their way through the swampy lagoon and the dense jungle, our castaways discover those buildings were part of an old hotel and resort that appears long abandoned.

Here, the group splits up and starts exploring. Dobbs and Chuck find the kitchen, where they poke around for a bit. They also find an aquarium -- and since the fish inside it appear pretty healthy, that can only mean one thing: they’re not alone here.

Then, almost on cue, the air is suddenly filled with the bombastic sound of Richard Wagner. Drawn to the source of the music, our group congregates in the main hall and slowly surrounds an old Victrola. When the record winds down, a voice with a slight Germanic accent calls from the shadows, asking, What are they doing here?

And after a few more cryptic questions, our refugees explain their predicament. But when Keith mentions they were hit by a freighter, the man behind the mysterious voice finally shows himself and demands to know the name of that ship.

Told it was the Proto-something-or-other, when the German (Cushing) verifies it was The Praetorious, he quickly disappears into the shadows again. Unable to find him, after having a long and taxing day, the stranded boaters pack it in, pick out a room, settle in for the night, and will continue their search in the morning and, hopefully, find a way off this island.

Meanwhile, back in the water, in that rusted-out derelict, something has finally broken out of the hold and are now moving freely about on the ocean floor, gradually circling ever-closer toward the island, where I believe our unwitting castaways are about to find out what exactly happened to that missing SS unit...

A native of Queens, New York, Ken Wiederhorn attended Kenyon College in Ohio until he dropped out during his sophomore year, moved back home, and got a job as a mail boy at the CBS Television Network, where he quickly worked his way up from the mailroom to a gopher in the newsroom, to an editor, and, eventually, an associate producer for the network’s documentary news series, CBS Reports.

Meantime, according to an interview on the Master Cylinder website, it was while still working as an assistant editor at CBS when Wiederhorn decided to go back to school. Seems a documentary filmmaker he had worked with had just been appointed head of the film department at Columbia University, who was able to shepherd him into the program. Here, Wiederhorn struck up a friendship with fellow film student, Reuben Trane; and together, they collaborated on a short film for their senior thesis, Manhattan Melody (1973), which earned them the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences’ inaugural Student Film Award. “Don’t call it an Oscar,” Wiederhorn later clarified. “It was more of a block of wood with a name-holder on it."

After graduating, Wiederhorn continued to work at CBS while Trane moved back home to Miami, Florida, where he started teaching a filmmaking course at Florida International University. All the while, Trane nursed a notion to take the next step and finally reached out to Wiederhorn to see if he wanted to collaborate again -- this time on a low-budget feature film. He did. And so, Trane looked to his family for financial backing, who had made a fortune in the heating and cooling business since creating the Trane Comfort Corps back in 1913. And they agreed to back Reuben’s efforts to the tune of $200,000.

As for the subject matter, it was quickly decided by Trane to follow the same path as many other independent productions before them, meaning an exploitation film or a horror movie were in order because it would be easier to sell, make their money back, and hopefully open a few doors to make something a little more ambitious later. In a 1975 interview with The Miami Herald, Wiederhorn commented on how horror was the only genre left for which there was a built-in market. Plus, “No matter how bad they are, horror movies make money,” Trane added.

Thus, the two formed a production company, and the first order of business was to get a script written. And for that, Wiederhorn, who freely admitted he wasn’t a fan of the genre, teamed up with John Harrison. Drawing inspiration from the Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier exposé, The Morning of the Magicians, one of the first books to explore The Thule Society and the Nazi party’s fascination with the occult and the supernatural, which led them to the idea of the German high command resurrecting dead soldiers through some dubious alchemy and turning them into a zombie attack squad.

By now, the decision had been made to shoot in Florida, with an inexpensive crew made up of Trane’s eager students; and since Trane was also good with boats, the ocean became a story element. And with that, Wiederhorn suddenly had the hilarious notion of a battalion of these Nazi zombies invading Miami Beach. And then, with the “help of a few more joints” their script really started taking shape, turning those undead Nazis into aquatic zombies -- a unique twist, which beat Fulci to the punch by over four years, who could move freely underwater, stalking the ocean floor, from which they terrorize a group of stranded tourists on some uncharted desert isle.

And so, the fledgling production company was rebranded as Zopix (-- Zombie Picture, get it?), and with the script finally finished, shooting was almost ready to commence. Trane would serve as producer and cinematographer on dry-land, Wiederhorn would direct, and Irving Pare would handle the underwater scenes. Also on board as the production's still photographer and production assistant, was future sleaze merchant Fred Olen Ray, who, like the others, was working on his first feature. And in an interest to save money, the decision was made to shoot the film in 16mm with the intent to blow it up to 35mm once (and if) they found a distributor for their film, which was shot under the title, Death Corps.

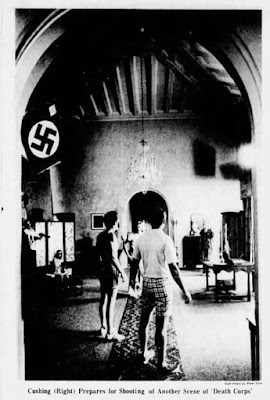

To add some weight to the marquee and hopefully overcompensate for their own inexperience, both Wiederhorn and Trane knew they needed to get a couple of genre vets to anchor the film. Money was tight, but they stretched it out a bit by relegating each star to only one half of the movie. Both John Carradine and Peter Cushing worked for five days each on the film for the sum of $5000 a piece -- though Cushing also demanded and received first class air travel and accommodations.

Apparently, according to several after action reports, Carradine, working on his 450th feature, was a bit of a grumpus, nearly drowning while filming his death scene in the Trane swimming pool, and was happy to be killed off early.

Cushing, on the other hand, was always the gentlemen, always prepared, and always willing to help out these novice filmmakers with suggestions on camera placements or character movements, which was much appreciated.

“A lot of times Cushing had a better idea of what we wanted than we did,” said Wiederhorn. The British actor was also fascinated with a certain American Institution -- the International House of Pancakes, and began each day by eating a stack of wheat cakes at the IHOP.

As for the rest of the cast, Brooke Adams was signed up in New York. This would be her first starring role, and she was about to break out a bit in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) and Philip Kaufman’s remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978). The rest of the small cast were recruited locally in Miami and the surrounding area, including Luke Halpin, whom we old farts will remember as Sandy Ricks from the old Flipper TV-series.

But the production’s biggest coup was probably securing the use of the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables. An old luxury resort first built back in 1924, it had served Presidents, movie stars, and notorious gangsters -- before he became Tarzan, Johnny Weismuller served as a swimming instructor there, teaching Al Capone’s son how to swim. When World War II broke out, the Biltmore was converted into an army hospital, and it remained a veteran’s facility until 1968, when it was shut down -- more like abandoned, shuttered, and sold off to the city.

And there it sat -- along with its sister hotel in Palm Beach, empty and unoccupied, until Wiederhorn and Trane managed to coax the owner, John D. MacArthur, the city fathers and “the powers that be” into letting them film in both locations for $250 a day.

Of course, the hotels had no power or plumbing. And with only one Winnebago on set with only one working restroom meant a lot of the toilets were used anyway, causing the production to move deeper and deeper into the hotel to get away from the smell as things dragged on. After filming wrapped, the property remained dormant until a massive restoration in the mid-1980s saw the Biltmore reopened and returned to its original grandeur.

They were also able to get some cheap production values with the wreck of the SS Sapona, a concrete cargo steamer that ran aground near Bimini during a hurricane in 1926, which served as the Nazi-zombies base of operations.

And for the beaches, jungles and swamps they used the mucklands of Matheson Hammock Park in Coral Gables and Crandon Park Beach in Key Biscayne. “I personally really hated the locations because they were really difficult to work in terms of physical comfort,” said Wiederhorn. “It was hot, it was humid and we would have to cover ourselves with mosquito repellent several times a day."

And it was within these hot, muggy, and snake-infested environs, shooting for 35-days between July and August, 1975, that a dozen or so ghastly creatures garbed in Wehrmacht uniforms and black goggles slowly rose from the bottom of the sea, surfaced, and headed inland in one truly spectacular sequence.

One by one they pop-up from the water, and as these undead automata begin trudging toward land, en masse, deadly silent, methodical and ruthless, they honestly bring to mind the ghostly Templars from Armando de Ossorio’s Tombs of the Blind Dead (1972) -- and we’ll be referring to them from here on out as the Aqua-Nazis.

Unaware of this development, as the sun rises, and apparently stuck indefinitely, Keith sends Dobbs on a mission back to the Bonaventure for some needed supplies. But as he makes his way back to the beach through the chest-deep lagoon, the cook soon realizes he is no longer alone as the Aqua-Nazis have him surrounded and quickly move in for the kill, inadvertently herding their victim into a cache of deadly sea urchins, robbing them of their prey.

Meantime, back at the hotel, Keith spots the old German, manages to corner him, and finally gets some answers. Told they must all leave immediately, Keith is more than happy to oblige if he’ll only explain how -- which he does, saying there is a small boat hidden in a nearby cove that should get them to safety. But they must hurry, for there is danger here. Danger in the water.

Alas, this warning comes too late for Rose, as she goes for another swim and bumps right into Dobb’s corpse. And after Chuck and Keith drag the body ashore, they find a torn SS insignia clutched in the dead man’s hand. And while Chuck contends that means the old German must be responsible, Keith isn’t so sure and says to maybe ask them, pointing out two Aqua-Nazis observing them from a distance before they slowly disappear beneath the water. With that, the men of the party confront the old German, who can’t believe they’ve wasted all this time and still aren’t off the island yet; and now he fears it may be too late -- for everybody.

Admitting that he did kill Dobbs, albeit indirectly, the German explains how he was in charge of that top-secret operation to create those Nazi super-soldiers, where they experimented on hoodlums, thugs, and murderers, turning them into monsters. Not dead -- but not alive either, he explains. And eventually, they engineered a perfect batch of specimens that were impervious to heat or cold. Calling them the Toten Korps (-- translated as the Death Corps, ‘natch), the SS tried to use them in battle but soon found out they couldn’t be controlled when these monsters turned on their masters, eventually killing everybody.

By the time this disaster was corralled and cleaned up, the war wasn't going well for Germany; and so, our mad scientist took the last batch of deviants, engineered to breathe underwater to be the ultimate U-boat sailors, and escaped capture on The Praetorious. But when word came that Germany had surrendered, fearing his creations would go haywire again, the order was given to scuttle the ship, sending his damnable creations to the bottom of the ocean.

As the architect of this madness, he then took up exile on this deserted island to keep watch, just in case, but he honestly thought he’d destroyed them for good. He was wrong. And when these interlopers don’t believe a word he’s said, the old man pulls a pistol and gives them two choices: get off the island, or he will shoot them all himself.

Taking this threat seriously, as the castaways go to search for that promised boat, the German seeks out and finds his old squad of Aqua-Nazis, who ignore his calls and disappear into the surf. Undaunted, his search continues until he stops to rest, bending over to take a drink out of a fresh-water stream, but then spots, too late, one of his creations just below the water’s surface. (Nice knowing you, Scary German Guy.)

Once the old boat is secured, our group has to navigate it out of a swampy tide-pool to get to the open ocean and make their escape. Breaking out of the trees, since they appear to be home free, Keith sets the small sail but the water is still too shallow. And as the boat keeps getting hung up on sandbars, they all must bail out and push the vessel toward deeper water.

Beverly is the first to notice the Aqua-Nazis are right behind them, so it’s only fitting that she’s the one who stumbles and falls behind. As Norman and Chuck abandon the boat to rush back to her aid, since the water’s finally deep enough, Keith tosses Rose into the boat to man the rudder while he heads back to help out, too.

But as the men manage to gather up Beverly, luck is against them again as the wind whips the sail around, knocking Rose out of the boat. And as the unmanned craft heads swiftly out to sea, Keith frantically swims after it but quickly realizes this is a lost cause and swims back toward shore.

Well ahead of him, the others make it back to dry land but apparently got separated. And as Rose tries to calm a frantic Norman down, who desperately wants to know if his wife is safe, they decide to head back to the hotel. (Okay, so maybe old Norman isn't such an asshole after all. And I'm truly amazed he's lasted this long.) But in his panicked state, Norman leaves a floundering Rose well and far behind in his wake. Soon out of sight, she calls for him to wait up, but he can’t hear her anymore.

Then, the Aqua-Nazis turn their goggled-sights on Rose, giving us an extended stalk-n-chase scene that leads us all the way back to the hotel, where she tries to hide by the swimming pool but the damned things are in there, too!

But as one of them grabs her, our heroine manages to rip off it's goggles, which proves most productive -- for its eyes are now exposed to the sunlight, causing the creature to scream in pain as it collapses and “dies,” which also causes the other Aqua-Nazis to retreat.

When the others reach the hotel -- and for the record, Chuck and Beverly found Norman’s body, and gather up Rose, who, alas, doesn't put together the lethality of removing those goggles from these predators, they decide to hole-up in the kitchen's huge walk-in freezer, rigged to lock from the inside, just as those water-logged bad guys start sloshing around the hotel, hunting for them.

But their refuge is not quite big enough as Chuck’s acute claustrophobia soon gets the better of him. And as he begs to be let out, Keith won’t comply until Chuck threatens to shoot him with a flare gun.

Once they let him out, the manic man also demands their only flashlight. But Keith refuses, and then slams the door shut, catching Chuck’s arm in the jam -- the same arm that was holding that flare gun, which pops off into this enclosed space. And when the flare’s fire and smoke drives everyone out, the weasley Chuck steals the coveted flashlight and flees.

Meantime, blinded by the flare-gun’s flash, Beverly stumbles off into the darkness alone -- though not as alone as she thinks, while Keith and Rose head deeper into the hotel's basement. Chuck, meanwhile, manages to make it outside only to fall into the swimming pool -- where several Aqua-Nazis are waiting. And while he puts up a good fight, and almost manages to climb out, he is ultimately dragged back under the fetid water and drowned.

Come the dawn, in an ironic twist (-- that all of the filmmakers failed to realize), Rose and Keith manage to survive this Night of the Soggy Dead and evade their Aqua-Nazi tormentors by hiding inside the hotel's massive coal furnace. Wow. And wow again.

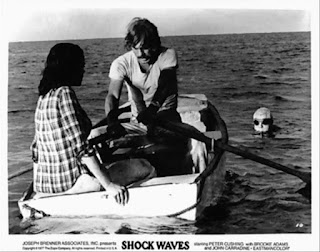

All seems quiet as they find poor Beverly, drowned in that aquarium, and then Chuck’s body floating in the pool. After that, the Aqua-Nazis are soon swarming and attack, chasing the surviving couple as they abandon the hotel and run for the beach, where they jump in the glass-bottom dinghy and try to row out to sea.

But the going is too slow, and though Keith manages to fight off the first two Aqua-Nazis, the third pulls him over the side and under the water. In the boat, Rose waits a few silent beats, scanning the water, but then sees Keith’s body floating underneath her.

This proves too much for the girl, who screams and then passes out as the boat drifts out to sea.

And as our flashback ends, we catch up with Rose at the hospital, where she appears to be jotting down these memories in a journal; until we realize that she keeps repeating the same thing over and over again. And then we pan around to see that all she’s been writing down is a bunch of gibberish. Turns out Rose is no longer with us.

When a small Want Ad ran in The Miami Herald in the early summer of 1975, looking for extras for an independent horror movie destined to be shot in their fair city, which needed mean looking men with strong Germanic features, Jay Maeder, a reporter and columnist for the newspaper, was tagged by his editor to go out and cover these auditions, thinking it would make a swell human interest feature.

Now, Maeder was a bit of a throwback when it came to journalism and a bit of an odd duck when it came to his People Column, which was described in his 2014 obituary as a blend of irreverence, gossip and frippery. “Everyone lives life in 3-D, [Maeder] kind of wrote about life in 4-D,” said his former editor, John Brecher. “Whatever the story was that you asked Jay to do, you could count on the fact no one in the world would write the story the way Jay Maeder would write it."

But it wasn’t just features, as news photographer Battle Vaughan pointed out in the same obit. “He was a reporter unlike any I’d ever worked with. He could get into anywhere, fit in, and report back with both laser precision and a mastery of language.” As an example, Maeder once went undercover and joined a group of homeless people who were being recruited by a cult, exposing a conspiracy to use them to swell the voting rolls in a rural county. Thus, Maeder would not go to the audition just to cover it but instead neglected to announce he was a reporter at all and just auditioned for a part himself.

About 25 men showed up, and Maeder, along with about eight others, were pulled from the line and told to leave a name and telephone number. Not much to write about, so the story was shelved until about a month later when Maeder got a follow-up call and reported to the office of Reuben Trane, who explained what the role would entail: being not only a zombie, but an underwater Nazi zombie; and then revealed a photo of the prototype make-up that would be involved.

Wiederhorn was also there, and made it clear it was going to be long hours, dirty work, with a lot of time in and under the water -- most of it in stagnant bogs or tepid lagoons filled with who knows what, and all kinds of things crawling and creeping within them -- and every one of them would bite.

Maeder agreed to all of the above and a few days later he was issued a Nazi uniform and sent to a Cuban beauty school and salon to get his hair shorn off and bleached white; a chemical process that was really quite painful. And as the shoot dragged on, Maeder would often slosh into the office, not-so-fresh from the set, and prowl around the newsroom in “fetid, swamp-rot Nazi regalia."

About halfway through the shoot, Maeder finally came clean and revealed who he was and why he was there. Both Wiederhorn and Trane had no objections, of course, figuring any publicity was good publicity at this point. And so, Maeder’s column, I Am a Zombie: Confessions of an Extra in Low Budget Death Corps, was published in the August 10, 1975 edition of the Miami Herald, one week after shooting wrapped.

In the article on the front page of the Lively Arts section, Maeder goes into much detail about the production, interviewing Wiederhorn and Trane -- crediting Wiederhorn with an extraordinary talent for finding unimaginably stagnant ponds, sewer canals, and other revolting bodies of water to shoot his movie in. He also talks about the two famous stars destined to headline the film and its ever-revolving title -- Death Corps, The Dead Don't Die, Sea of Fear, Black Sand, Nightmare Island, Island of Doom, Monsters of the Third Reich, Almost Human, and finally, Shock Waves (1977).

But the majority of the writing concerns himself and the trials and tribulations he and his fellow Death Corpsmen faced while filming, including his big scene, where he kills Jack Davidson, who played Norman.

“We Death Corpsmen seem to spend a lot of our time crouching underwater,” said Maeder in his after action report, “biding our time until one hapless victim or another stumbles past. Busy busy busy. If it’s one thing we’ve got here, it’s hapless victims … Up from the murky depths I come, crashing through waste deep water … Fingers like steel bands around his hapless throat. The mighty strength of a Death Corpsman. The bulging eyes of the victim. Death in the bright afternoon.” Well, at least until the director called for a cut because he’d botched something. Again.

Yeah, it took four takes to get that scene right. On the first, Maeder blew his cue on when to surface. The second, it took too long for him to catch up to Davidson and they were hopelessly out of frame. And the third was Davidson’s fault, anticipating his fatal submersion too much. The fourth take, was good enough. For his efforts, Maeder and the other Aqua-Nazis were paid $25 a day. And while he seemed genuinely proud of his efforts, the reporter made it clear the majority of the credit should go to Alan Ormsby, the make-up man behind the Death Corps signature look.

Ormsby was a drama student at the University of Florida when he first met Bob Clark. And these two would go on to collaborate on the low-budget zombie movie, Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things (1972), which he co-wrote, starred in, and did the zombie make-up for. Shot in Miami, the film is both cheap and obnoxious and yet startlingly effective with its chills. Clark and Ormsby would follow that up with Deathdream (1974), a twisted tale based on W.W. Jacobs’ The Monkey’s Paw, which Ormsby had adapted into a screenplay and supervised the special make-up effects, breaking in some novice named Tom Savini.

He had just finished shooting Deranged (1974) up in Canada, a creepy take on the notorious necrophiliac and body snatcher, Ed Gein, which Ormsby wrote, co-directed, and once again supervised the make-ups for; but he had a falling out with Clark, who was the film’s uncredited producer, who shut his old friend out of the post-production phase of the film. And so, he was available. And more importantly, he was back home in Miami.

Of course, being unfamiliar with horror films, Wiederhorn wasn’t really aware of what Ormsby had done. But they screened Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things and he immediately took a liking to Ormsby, finding they were very like-minded when it came to injecting humor into these horrific proceedings. And aside from the requirement that they had to wear those goggles to provide some form of vulnerability, Ormsby pretty much had a free hand in the designs of the Aqua-Nazis. There were plenty of concerns at first due to the requirements of the make-up holding up underwater, but with several tweaks and a few additives the make-up held together splendidly, resulting in something relatively simple, unique, and extremely effective.

Maeder described the make-up call as “devoting an hour every morning at the table of the Winnebago,” where Ormsby would apply “warts and festering sores and harelips and thick layers of latex and greasepaint.” Playing these zombies were Maeder, Bob Miller, Talmadge Scott, Gary Levinson, Sammy Graham, Preston White, Reid Finger, Donahue Guillory, Mike Kennedy, Robert Miller and Tony Moskal.

Moskal, according to both Maeder’s article and Wiederhorn’s director’s commentary on the Blue Underground DVD of Shock Waves, was very much at home in the water and quickly established himself as the prime Aqua-Nazi, winning “the boundless respect of Wiederhorn and Trane” for his intensity and devotion to every scene he was in. “The rest of us were clods,” said Maeder, “who couldn’t do anything right.”

One of his co-stars couldn’t help wiping his nose whenever he surfaced; another couldn’t stop giggling when he was supposed to attack someone; and apparently it was very difficult to see through those darkened goggles, so these deadly Death Corpsmen tended to bump into each other. A lot. And Maeder claimed that he, himself, at some point or other, tripped over every mangrove root in Matheson Hammock.

And while I do feel Wiederhorn goes back to the well a few times too many with all the cutaways to the Aqua-Nazis lurking under the water, or slowly rising out of the surf only to slowly return under the surf. But I’ll be damned if each one isn’t effective or lacks impact as they stealthily pop out of nowhere and attack. And a lot of credit needs to go to this pack of “screw-ups” for these marvelously eerie set-pieces -- and I never saw a single air bubble escape from the whole lot of them.

When filming wrapped, Wiederhorn took all of the footage back to New York, where it was edited together by Norman Gay, who had worked with William Friedkin as an associate editor on The French Connection (1971) and was nominated for an Oscar for his work on The Exorcist (1973). Wiederhorn was also responsible for bringing in fellow Columbia grad, Richard Einhorn, to do the soundtrack for the film, whose minimalist electronic score really gets under your skin and helps glue the film together into a bizarre trance-like state, which is only enhanced by the grain of the film being blown up to 35mm, giving things a strange, waking dream vibe.

When it was finally finished, there was a long delay before Shock Waves was finally released. Of course, there had been a lot of interest from distributors -- most prominently, Crown International, but Trane was smart enough to have the family lawyers go over the contracts first for any irregularities or “black holes” that would eat into their share of the profits.

They finally settled on Joseph Brenner, whose company handled the likes of Cheri Cafaro’s Ginger McAllister trilogy -- Ginger (1971), The Abductors (1972), Girls Are For Loving (1973), and foreign imports, ranging from Umberto Lenzi’s Sacrifice (1972) and Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) to the Shaw Brother’s totally mental Infra-Man (1975). And so, nearly two years after it wrapped, Shock Waves finally made its theatrical debut in July, 1977, where it ran into a little competition from Peter Cushing’s other film that came out that year. Perhaps you’ve heard of it?

Still, as Maeder put it in his article, “[Shock Waves] does not promise to be an especially bad film or, the implausibilities notwithstanding, even a merely silly one: Even in rough footage it emerges as a genuinely gripping little flick graced by the atmospherics of the Wiederhorn-chosen locations -- including the ravaged Biltmores in Coral Gables and Palm Beach as well as the mucklands of Matheson Hammock and Key Biscayne.” He wasn’t quite as kind in his follow up review of the film in 1977, though; but Maeder still called the film a good time to be had by all since “the killing and related unpleasantry are relatively bloodless since Zopix was going for a PG-rating."

“We’re ready for TV without any major changes,” said Trane. Yeah, unlike Florida’s earlier exploitation scene, where the likes of Hershell Gordon Lewis or Richard Flink shoveled all kinds of gore and bodily dismemberment onto movie screens, Shock Waves isn’t very gross or bloody. There were a few attempts to add some punch, including some failed squibs, but with no money to try again these notions were soon abandoned. Said Wiederhorn, “We knew going in that we did not want to get into a lot of bloody special-effects because we were making a low-budget movie, and it seemed to me that the way to succeed was not to become overly ambitious. To really make sure that what we were doing was something that we could in fact do."

As for Trane and Wiederhorn post-Shock Waves, well, the former got out of the business altogether and took up a highly successful career as a boat-builder after their next feature, King Frat (1979) -- an obnoxious Animal House (1978) knock-off that, despite a few moments of genuine hilarity, really didn’t go anywhere. Wiederhorn, meanwhile, stayed in the game, turning out the effective thriller, Eyes of a Stranger (1981), even though his producers insisted against his wishes that his strangler be turned into a knife-wielding psycho and to bloody things up to cash-in on the current Slasher craze, before flaming out with a couple of sequels, Meatballs II (1984) and Return of the Living Dead II (1988).

But, these two still gave us Shock Waves. And while they never did get around to invading Miami Beach, what Wiederhorn, Trane, and Ormsby, and all the others managed to pull off on their limited budget was a strange little bugaboo of a film; a fever dream, really, where things don’t quite add up logically, which only adds to the dread and a strange sense of unease and unreality.

Thus, this film tends to stand out because it looks and behaves so differently, bringing to mind Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962) on one hand, and on the other, when you combine the tropical setting, the zombified antagonists, and the pulsing electronic score, there is a definite prescient Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1979) vibe coming off this thing, too -- just not quite as gory and without all the eyeball trauma.

Thus, despite a few minor quibbles and a few glitches in continuity, and the fact that I honestly believe a youthful first impression of catching this feature on The Late Late Show might be shadowing my favorable opinion on this flick just a bit, I still deem Shock Waves an offbeat gem and a creepy afternooner that is just begging to be wasted on your TV screens.

Well, if you don't know what Hubrisween is by now, Boils and Ghouls, I don't think I can help you. Anyhoo, that's 19 films down with seven yet to go. Up next, this time Venus invades Earth, and they brought a few adorable robots with them.

Shock Waves (1977) Zopix Company :: Joseph Brenner Associates / P: Reuben Trane / D: Ken Wiederhorn / W: John Kent Harrison, Ken Pare, Ken Wiederhorn / C: Irving Pare / E: Norman Gay / M: Richard Einhorn / S: Brooke Adams, Luke Halpin, Fred Buch, D.J. Sidney, Jack Davidson, John Carradine, Peter Cushing

No comments:

Post a Comment